A Tar Pits Travelogue

Tar pits, more accurately known as asphalt seeps, are rare. And I couldn't leave Oklahoma without knowing if we had missed one.

By Alexis Mychajliw

The past year of the pandemic has been defined by many things, including a never-ending email chain of fieldwork deferrals that has lingered in the inbox of nearly all the scientists I know. With my own trip to study the tar pits of Trinidad on pause, it was with incredible curiosity that I learned of a new potential tar pit: one not half way across the world, but instead just an hour from where I was living at the time as a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Oklahoma.

Tar pits, more accurately known as asphalt seeps, are rare. Forming by chance in all the right ways, they are places where geology intersects with biology to preserve time capsules of otherwise fragile and fleeting things. In Los Angeles, we can thank tiny organisms known as diatoms for dying in the Miocene (~15-5 million years ago), being cooked into oil, then moving upwards to entrap and preserve the remains of Pleistocene life (<50,000 years ago). Around the world, other such happy accidents (well, for paleontologists) have been discovered – first by Indigenous peoples, later by colonial oil seekers – in California, the Caribbean, South America, and Azerbaijan. Once you’ve been surrounded by literally thousands of asphaltic fossils in a single moment, as you are while sitting in the collections of Rancho La Brea, it can be easy to assume that we’ve found it all. The idea of “finding” a new tar pit felt a bit like discovering a new species of elephant—there’s no way we could have missed something so obvious, right?

We now recognize that so much information was lost during those historic excavations that form the backbone (ha!) of our collections. Bones were removed from their context, like sentences lifted from paragraphs of a burned book—we can appreciate them in isolation but may never know how they fit together. And so, the opportunity to see fossils “in the wild” is one I will never pass up, because such glimpses of preservation and context hold the potential to better reunite the few fragments we have of our former world.

So, by some luck, I found myself about an hour’s drive from the purported pit, once supposedly used by the Comanche and today located within the bounds of an active military base, Fort Sill. Oil production—intimately linked to tar pit presence—is so prevalent in Oklahoma that at times I felt like I was driving through forests of strange megafaunal birds, with oil pump jacks bobbing at their own pace alongside roads, mall parking lots, houses, and even schools. Yet if you search “Oklahoma tar pit” on the internet, precious few results are returned. With less than a month before I left the state, I could not move without knowing the answer to my question, couldn’t pass up my chance at the joy of re-situating something that has been hiding in plain sight. So, in lieu of a farewell party from the lab, I asked for a field trip—let’s go find a lost tar pit. Bonus: you get to poke asphalt with a stick.

Though commonplace to life in Oklahoma, I had never been on an active military base. After waking up before dawn to drive on back roads punctuated by a seemingly endless series of cattle grates (it turns out not taking the toll road is an adventure in itself), I arrived at the gate and proceeded with a background check. My key to entry, not unlike a visit to museum collections, was an unceremonious piece of white paper with an unflattering photo of myself and my clearance level.

Our expedition’s first stop was the Fort Sill National Historic Landmark & Museum, where we picked up some maps kindly provided by the curator, Gordon Blaker, and paused to appreciate the diversity of artillery artifacts. On the road again, our caravan was occasionally reminded of the need to studiously follow directions when we’d hear a pop or crash reminding us that we were indeed on an active artillery base. Yet while driving, my eyes were trained on the small streams bleeding through the grassy fields – such water movement is a good omen for asphaltic fossils. We finally arrived at a small pull-out area and lo and behold in true tar pits tradition, encountered a sign that someone had smeared with asphalt.

We instantly came upon what I had seen in the few photos available online: a small pond with a rainbow sheen and black goo collecting at the edges, an easy stand-in for the familiar Lake Pit at Rancho La Brea. But just like the Lake Pit, this was a red herring, “not the droids” I was looking for—pick your metaphor. I wanted to see where fresh asphalt and water come together, mix, and move through the landscape, eventually depositing entrapped treasures in sticky sediments for years to come.

As we descended the gentle hill, we found a creek that could easily have been a scene from my visits at the McKittrick Brea in California, the languid swirl of asphalt with streaks of brown and white crust producing a satisfying crunch beneath my boots. Bits and pieces of modern plants and animals sat mired and bleaching at the surface, waiting to be covered and transformed by time. This is what I was here for—I have arrived.

As we moved through the swale, the water’s path cut downwards and revealed the hydrocarbon-bearing rocks otherwise hidden by grass and soil. Just as you can visit the source of Rancho La Brea’s asphalt on the coasts of Santa Barbara where the Monterey lies folded and exposed, so too can you see the source of Fort Sill’s hydrocarbons. The Woodford Shale represents the Devonian (~350 million years ago) and is a deep chasm away from familiar Rancho La Brea fauna of the Pleistocene, and virtually all other tar pits that we have documented scientifically. And this is where things get murky, which means it is also where things get interesting.

Photo by A. Mychajliw

Check out that extremely crunchy crust, the liquid asphalt mixing with water, and the bright red rocks.

Photo by A. Mychajliw

I did advertise the adventure by promising one could poke asphalt with a stick!

Photo by A. Mychajliw

As we moved through the swale, the water’s path cut downwards and revealed the hydrocarbon-bearing rocks otherwise hidden by grass and soil.

Photo by A. Mychajliw

Some asphalt and crust from the McKittrick Brea in California, for comparison with Fort Sill, though taken at different seasons.

1 of 1

Check out that extremely crunchy crust, the liquid asphalt mixing with water, and the bright red rocks.

Photo by A. Mychajliw

I did advertise the adventure by promising one could poke asphalt with a stick!

Photo by A. Mychajliw

As we moved through the swale, the water’s path cut downwards and revealed the hydrocarbon-bearing rocks otherwise hidden by grass and soil.

Photo by A. Mychajliw

Some asphalt and crust from the McKittrick Brea in California, for comparison with Fort Sill, though taken at different seasons.

Photo by A. Mychajliw

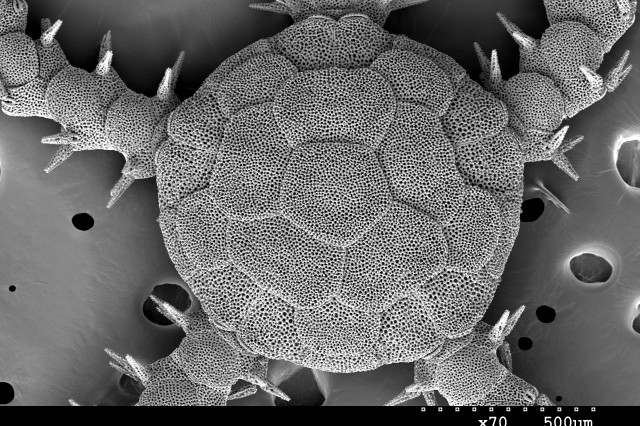

Let me remind you of what we do and don’t know about tar pits. We do know that they form when hydrocarbons percolate upwards from their source or temporary holding pen (reservoir) to reach the surface. There, they can entrap recently living organisms and mix with sediments and water to bury them deep underground for paleontologists to find. This means that the age of what is preserved (like a Pleistocene mammoth) is inherently limited by the age of the hydrocarbons doing the preserving (in this case, the Miocene preserves the Pleistocene), and the preservation is near instantaneous, geologically speaking. But we’ve recently learned through more careful study of geological context that some sites, such as Tanque Loma of Ecuador and Forest Reserve of Trinidad, instead represent a case where the asphalt was late to the game, so to speak. That is, by the time the hydrocarbons were moving around, fossils were already forming—the hydrocarbons permeated the bones of animals already dead and buried, protecting them for the future but unable to reverse the unfolding degradation, making the remains more fragile than what we’re used to at Rancho La Brea. Long story short: sometimes a sloth lies dead for thousands of years before the asphalt can reach it (Tanque Loma), other times it is the asphalt that traps the sloth (La Brea). Either way, the sloth loses, but paleontologists win.

You may now be wondering: what would Devonian hydrocarbons preserve? As you’ve now learned, something that happened more recently than ~350 million years ago, after the hydrocarbons formed. We have a small number of tantalizing clues that require some serious follow up. It turns out that while Oklahoma doesn’t have much from the Pleistocene like California, it is famous for its view of the dry Permian—the characteristic and unmistakable red dirt that highlights the edges of the roads in the state. True mammals had yet to appear on the scene, and instead Oklahoma was crawling with a menagerie of tetrapods from some extinct lineages like temnosponyls and pelycosaurs. Incredibly rich Permian assemblages are known from limestone quarries, like Richards Spur about 20 minutes north of Fort Sill, and some fossils from these porous rocks show hints (hints!) of a familiar friend – the charcoal black of hydrocarbons - the Devonian visiting the Permian, perhaps? Just a handful of these specimens exist from our focal site on the army base and are housed at the Sam Noble Museum of Natural History on the University of Oklahoma campus. As in any good mystery, these specimens prompt more questions than answers. Who collected these, and when? What was their context? What did they miss? And, what is still waiting for us to discover?