Year of the Horse

Celebrate the 2026 Lunar New Year, Year of the Horse, with highlights from the collection

The Lunar New Year 2026 ushers in the Year of the Horse, which is celebrated in many Asian countries such as China, Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Malaysia. In the story of the Jade Emperor’s race, the horse galloped swiftly to the finish line behind the rabbit and dragon. Unbeknownst to the horse, the snake hid on its hoof. It jumped out as the horse approached the finish line, spooking the horse and leaving the horse to finish in seventh place. Those born under the Horse are thought to be confident, agreeable, and responsible.

Celebrate the Lunar New Year with us as we invite you to gallop into a horse-inspired tour through the Museum's collections!

The Natural History of Horses

Horses are charismatically endearing creatures with a natural history spanning about 45 to 55 million years. They evolved from a small multi-toed creature, Eohippus, to the large, single-toed animal we know today. Although much of this evolution occurred in North America, where horses originated, they became extinct there about 10,000 years ago, only to be reintroduced in the 15th century.

Today, there are almost no truly wild horses, with nearly all free-roaming horses, including pony subspecies, Equus ferus, considered feral or semi-feral, having descended from domesticated lines, save for the Przewalski’s horse. With over 300 recognized breeds globally, horses have been developed anthropomorphically for diverse uses. These animals exhibit a remarkable adaptability, thriving in a variety of environments, from deserts and prairies to coastal marshes, which is evident in their specialized behaviors, diets, and physical traits.

Trotting through the Collection

Mane-ly Mammals

Beginning the tour is our Mammalogy department. Mammalogy is the study associated with recent mammals. Our collection comprises 98,000 specimens consisting of skins, skulls, skeletons, tanned hides, and fluid-preserved specimens of terrestrial and marine mammals. Our strengths include: bats, cetaceans, African ungulates, and local (Southern California) mammal species. Within our collection, you can find a number of specimens highlighting the variety of Equus, the genus horses share with zebras and asses.

Jacqui Estrada

Przewalski’s horse, or Equus ferus przewalskii, is the only true wild horse species remaining in the world, once extinct in the wild but successfully reintroduced.

Jacqui Estrada

This Mammalogy specimen is used by another department, Vertebrate Paleontology, to provide comparative data for reference when they look as fossilized horse material.

Photo By Shannen Robson

While most of its specimens are housed in jars or combine a box of bones along with collection skins, some of the earlier specimens in the Mammalogy Collection are pelts like these. As scientific techniques continue to progress, the ways in which specimens become useful to research keep expanding. Things like genetic analysis were unimaginable at the time most of these hides were added to the Mammalogy Collection.

1 of 1

Przewalski’s horse, or Equus ferus przewalskii, is the only true wild horse species remaining in the world, once extinct in the wild but successfully reintroduced.

Jacqui Estrada

This Mammalogy specimen is used by another department, Vertebrate Paleontology, to provide comparative data for reference when they look as fossilized horse material.

Jacqui Estrada

While most of its specimens are housed in jars or combine a box of bones along with collection skins, some of the earlier specimens in the Mammalogy Collection are pelts like these. As scientific techniques continue to progress, the ways in which specimens become useful to research keep expanding. Things like genetic analysis were unimaginable at the time most of these hides were added to the Mammalogy Collection.

Photo By Shannen Robson

Saddle Up for Anthropology

Anthropology is the study of humankind, both past and present. Here at the Museum, the Anthropology Department is responsible for curating archaeological and ethnographic collections collected by and donated to the Museum. The Archaeology Collection includes approximately 100,000 ancient artifacts. The majority of items in the collection are tools, decorative and utilitarian objects, included in the vast assemblage of materials, in addition to samples of shell, animal bone, soil, and plant remains that can be used to study past human adaptations. It’s through these collections that you can see the relationship that horses and humans have maintained through the years.

Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County

The location of where this ornament was collected, as well as its origin, suggest that trade with Arabic speaking peoples from North Africa was common.

Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County

Brindles and whips like this one were tools, used for controlling horses used in ranching and transportation, often made from horsehair.

Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County

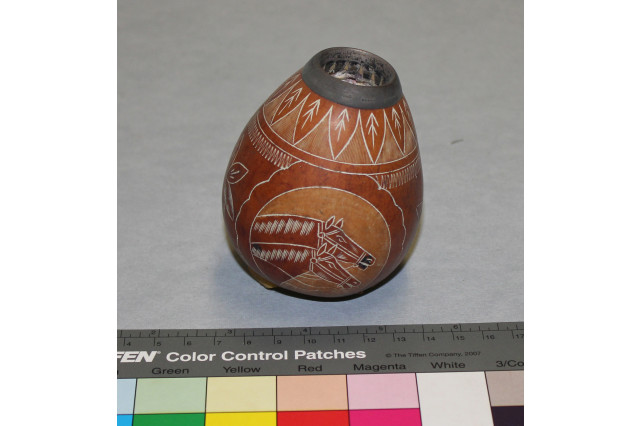

This horse-decorated cup made from a gourd is from Brazil (1910), where is was utilized for drinking mate, a traditional South American caffeine-rich infused drink, often shared socially.

Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County

This violin and horsehair string bow was made in Sisiguichic (1940) by the Rarámuri, a group of indigenous people of Chihuahua, Mexico,

Karen Knauer

This small horse carving is a Zuni fetish—a hand-carved animal figure believed in Zuni culture to embody the spirit and qualities of the animal it represents, crafted with care and traditionally used in prayer, protection, and ceremonial life. Zuni fetishes are part of a centuries-old Southwestern Native tradition of carving sacred animal allies from stone and shell, and the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County holds selections from the notable Boyd and Mary Evelyn Walker Collection of these powerful carvings.

1 of 1

The location of where this ornament was collected, as well as its origin, suggest that trade with Arabic speaking peoples from North Africa was common.

Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County

Brindles and whips like this one were tools, used for controlling horses used in ranching and transportation, often made from horsehair.

Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County

This horse-decorated cup made from a gourd is from Brazil (1910), where is was utilized for drinking mate, a traditional South American caffeine-rich infused drink, often shared socially.

Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County

This violin and horsehair string bow was made in Sisiguichic (1940) by the Rarámuri, a group of indigenous people of Chihuahua, Mexico,

Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County

This small horse carving is a Zuni fetish—a hand-carved animal figure believed in Zuni culture to embody the spirit and qualities of the animal it represents, crafted with care and traditionally used in prayer, protection, and ceremonial life. Zuni fetishes are part of a centuries-old Southwestern Native tradition of carving sacred animal allies from stone and shell, and the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County holds selections from the notable Boyd and Mary Evelyn Walker Collection of these powerful carvings.

Karen Knauer

Giddy Up for Malacology

In the Malacology Department, which focuses on the study of mollusks, the Museum has a diverse group of animals, including snails, clams, octopuses, and more. The Museum's Malacology Collection is global in scope, with a particular emphasis on species from the Eastern Pacific Ocean. This extensive collection comprises an estimated 500,000 individual items, representing approximately 4.5 million specimens. Among the treasures housed at the Museum, we encounter several mollusks named for their equine features.

Prance into Paleontology

Vertebrate Paleontology is the study of ancient animals that have a vertebrate column, otherwise known as a spine or backbone. Our Vertebrate Paleontology Collection is the fifth largest in the nation and a research standard for universities and colleges in the Southern California region. It's in this collection that we are able to see what horses in North America looked like 30,000 years ago.

Jacqui Estrada

Found in Gypsum cave in Nevada, this horse hoof and cast show how scientists can indicate where research samples were taken from a specimen.

Karen Knauer

Celebrating the Year of the Horse with a glimpse into deep time: this fossil skeleton of Equus occidentalis, the “Western horse” uncovered at La Brea Tar Pits, represents an Ice Age relative of the modern horse that once roamed North America during the Pleistocene. Its presence in our local asphalt deposits reminds us that the lineage of horses has deep roots in Los Angeles, long before domestic horses were reintroduced from Eurasia.

1 of 1

Found in Gypsum cave in Nevada, this horse hoof and cast show how scientists can indicate where research samples were taken from a specimen.

Jacqui Estrada

Celebrating the Year of the Horse with a glimpse into deep time: this fossil skeleton of Equus occidentalis, the “Western horse” uncovered at La Brea Tar Pits, represents an Ice Age relative of the modern horse that once roamed North America during the Pleistocene. Its presence in our local asphalt deposits reminds us that the lineage of horses has deep roots in Los Angeles, long before domestic horses were reintroduced from Eurasia.

Karen Knauer

Canter Into Ornithology

Venturing into the Museum’s Ornithology Collection, we encounter specimens that have close relationships with local equine species. The bird species below are only two of the 121,000 specimens in our collection, that represents over 5,400 species. The scope of the collection is particularly rich in species from North America, Africa, South America, and the Pacific Ocean. Among these treasures are cattle egrets and red-billed oxpeckers.

Eugene Eric Kim, iNaturalist

This small heron is often seen foraging near livestock and horses, earning it the name "Cattle Egret."

Thomas Hirsch, iNaturalist

The red-billed oxpecker, or Buphagus erythroryncha, has a symbiotic relationship with large mammals, feeding on ticks and other parasites.

1 of 1

This small heron is often seen foraging near livestock and horses, earning it the name "Cattle Egret."

Eugene Eric Kim, iNaturalist

The red-billed oxpecker, or Buphagus erythroryncha, has a symbiotic relationship with large mammals, feeding on ticks and other parasites.

Thomas Hirsch, iNaturalist

Making a Stable Impression in Marine Biology

The Museum's Marine Biodiversity Center curates our collection of marine invertebrate specimens, documenting global and regional invertebrate fauna (animals that lack a backbone). Our Marine Biodiversity Center staff are responsible for preserving these specimens and their associated data, which involves evaluating, applying curatorial procedures, and organizing information for incoming collections—either maintaining them in the Center or moving them to other Museum departments. It’s within this collection that we find specimens ranging from horseshoe crabs to horsehair worms.

Philip Precey, iNaturalist

Horseshoe crabs are ancient marine arthropods with helmet-like shells shaped like a horse’s shoe, though their closest relatives are actually spiders and scorpions! These ancient marine arthropods are often called "living fossils" because they have remained relatively unchanged for over 450 million years.

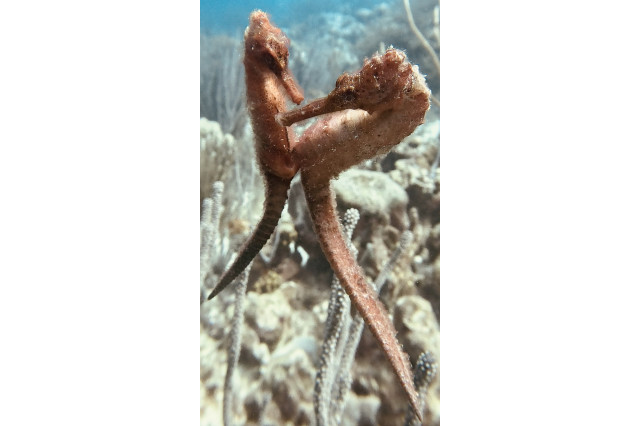

Horsehair worms get their descriptive name from their long, thin body shape that closely resembles the shape and size of a strand of hair from a horse's mane or tail. These parasitic worms have an unusual multi-stage lifestyle. Horsehair worms begin as eggs laid in water, spend most of their lives growing quietly inside insects like grasshoppers, then hijack their host’s behavior to drive them back to water, where the adult worm emerges to reproduce and start the cycle all over again.

1 of 1

Horseshoe crabs are ancient marine arthropods with helmet-like shells shaped like a horse’s shoe, though their closest relatives are actually spiders and scorpions! These ancient marine arthropods are often called "living fossils" because they have remained relatively unchanged for over 450 million years.

Philip Precey, iNaturalist

Horsehair worms get their descriptive name from their long, thin body shape that closely resembles the shape and size of a strand of hair from a horse's mane or tail. These parasitic worms have an unusual multi-stage lifestyle. Horsehair worms begin as eggs laid in water, spend most of their lives growing quietly inside insects like grasshoppers, then hijack their host’s behavior to drive them back to water, where the adult worm emerges to reproduce and start the cycle all over again.

Sea These Ponies in Ichthyology

Hold your horses! Next, we visit Ichthyology. Our fish collection is one of only ten internationally recognized ichthyological collections in the United States, housing nearly three million cataloged specimens that represent most fish families. Within this vast collection, we find the genus Hippocampus, home to the seahorse. Named for their distinctly horse-like heads, these fish are unique for another reason: the males possess a specialized brood pouch where they store fertilized eggs until the young fry are born.

Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County

This Pacific seahorse (NHM Specimen No.38097-3) was collected in 1974 from Magdalena Bay off the Eastern Pacific Coast of Baja, Mexico. One of the largest seahorses in the world—growing up to 12 inches in length—this species' scientific name, Hippocampus ingens, means "horse (hippo) sea monster (kampos)" in Greek.

Jürg, iNaturalist

Seahorses are true fishes that happen to share a resemblance to horses with their curved neck and head, and elongated snout. The seahorse's straw-like mouth helps it "slurp" up microscopic plankton for food. Unlike an actual horse, a seahorse's tail is prehensile—capable of grasping and holding onto objects. This Pacific seahorse curls its tail around an underwater plant, preventing it from floating away in the current.

Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County

Longsnout seahorses, Hippocampus reidi, (NHM Specimen No.6246) live in mangrove, seagrass, and shallow coral habitats of the Western Caribbean. While preserved specimens (like this one) lose their natural color over time, in the wild, longsnout seahorses have the ability to change color patterns when they need to blend in with their environment. This helps the seahorse sneak up on unsuspecting prey and protects them from larger predators lurking nearby.

jootjevdtoorn, iNaturalist

Seahorses are unique among animals in that the males, not the females, give birth to their young. This is made possible by the fact that male seahorses have external pouches and females do not. When seahorses mate, the female produce unfertilized eggs, which she deposits inside the males pouch (as seen here on the left, between two Longsnout seahorses). The male then internally fertilizes those eggs and broods, or incubates, them until they are ready to hatch and swim out of the pouch.

1 of 1

This Pacific seahorse (NHM Specimen No.38097-3) was collected in 1974 from Magdalena Bay off the Eastern Pacific Coast of Baja, Mexico. One of the largest seahorses in the world—growing up to 12 inches in length—this species' scientific name, Hippocampus ingens, means "horse (hippo) sea monster (kampos)" in Greek.

Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County

Seahorses are true fishes that happen to share a resemblance to horses with their curved neck and head, and elongated snout. The seahorse's straw-like mouth helps it "slurp" up microscopic plankton for food. Unlike an actual horse, a seahorse's tail is prehensile—capable of grasping and holding onto objects. This Pacific seahorse curls its tail around an underwater plant, preventing it from floating away in the current.

Jürg, iNaturalist

Longsnout seahorses, Hippocampus reidi, (NHM Specimen No.6246) live in mangrove, seagrass, and shallow coral habitats of the Western Caribbean. While preserved specimens (like this one) lose their natural color over time, in the wild, longsnout seahorses have the ability to change color patterns when they need to blend in with their environment. This helps the seahorse sneak up on unsuspecting prey and protects them from larger predators lurking nearby.

Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County

Seahorses are unique among animals in that the males, not the females, give birth to their young. This is made possible by the fact that male seahorses have external pouches and females do not. When seahorses mate, the female produce unfertilized eggs, which she deposits inside the males pouch (as seen here on the left, between two Longsnout seahorses). The male then internally fertilizes those eggs and broods, or incubates, them until they are ready to hatch and swim out of the pouch.

jootjevdtoorn, iNaturalist

These collections not only celebrate the diversity of our Museum collections but also provide critical insights into their cultural and ecological significance. Whether studying the wild horses of North America's past or marveling at how long horses have held significance to humans, the Museum's collection of archives continue to inspire awe and advance scientific understanding.