L.A. ON WHEELS SCAVENGER HUNT

Explore the collections of the Natural History Museum through the lens of wheels!

As the oldest natural history museum on the West Coast, we were bound to find some examples of wheels in our vast collections. However, not all of our examples might be what you are expecting. From wheel snails to motorized carriages, take a virtual tour below to see how this ubiquitous structure—found in nature and human-made structures—is represented in our collections.

Roly-polies or pill-bugs (Armadillidium vulgare) get their names from the ability to roll into a tight round ball to protect themselves. When an animal rolls itself into a ball shape, it’s called conglobation (what a fun word!). This acts as an important defense against predators and heat stress (trapping moisture inside the ball to reduce water loss). Roly-poly conglobation is made possible by segmented, overlapping plates that give their armor-like exoskeleton more flexibility.

Catherine Fox

The Museum’s Bugtopia exhibit houses a terrarium of about 50 common roly-polies. These little critters grow to be about 0.4 inches (10 mm) in length and weigh less than an ounce (0.12 g)! On average, roly-polies live up to 1.5 years. You’ll have to look hard to find all of them, as they are excellent at hiding under debris and camouflaging in their environment.

Lisa Gonzalez

Roly-polies are a type of terrestrial crustacean known as an Isopod, meaning they have multiple pairs of identical-shaped legs. Like all crustaceans (think crabs and lobsters), roly-polies have a tough outer exoskeleton that protects their thinner, more vulnerable underbelly and 14 little legs. This preserved pill-bug specimen (Armadillium spp.) from the Museum's Living Collections allows you to easily count all seven pairs of legs.

Franco Folini, Wikimedia Commons

Roly-polies have a series of overlapping plates, visible here, in their tough exoskeleton that give their body more flexibility. This feature allows them to roll into a protective ball in order to defend themselves against predators.

Franco Folini, Wikimedia Commons

Today, roly-polies can be found worldwide in moist temperate climates; however, they were originally native to the Mediterranean. They are so successful at adapting to terrestrial ecosystems that they can be found almost anywhere there is soft, damp soil. Because they're so easy to find, many young bug enthusiasts first start observing bugs thanks to how cute and gentle roly-polies are!

Michel Vuijlsteke, Wikipedia

This hard outer exoskeleton, along with a fairly bitter taste, helps protect roly-polies from most predators. But there is one predator they have a hard time escaping from: the roly-poly killer (or woodlouse killer) spider, pictured here. This spider (Dysdera crocata) evolved alongside roly-polies in the same environment; as such, they became specialized predators that have enlarged chelicerae (clasper-like jaws) perfect for piercing through the hard exoskeleton of their prey…like roly-polies. These spiders are ambush predators, hiding in the leaf litter and under rocks to sneak up on roly-polies passing by.

Catherine Fox

The Museum's roly-polies can eat pretty much any organic matter (microorganisms and detritus) they find in the dirt, as long as the soil biome has leaf litter and fungus. Roly-polies are important detritivores: animals that eat dead and decaying organisms such as leaf litter, fungus, and animal poop. Detritivores improve soil quality by recycling nutrients back into the soil.

Lisa Gonzalez

Roly-polies have such a positive effect on their ecosystem that the Museum's Living Collections use them in their bioactive (living) terrariums to break down matter and enrich the soil. Bioactive terrariums are ones where different organisms are added to the soil to mimic what naturally happens in the outdoors. Along with springtails, other isopods, and mycelium fungus, roly-polies help the Museum maintain the health of its Living Collections. Roly-polies live alongside the Museum’s stick bugs—like the Malaysian jungle nymph (Heteropteryx dilatata) pictured here—snakes, and skinks to feed off of the larger animals' droppings and clean the enclosure. Roly-polies that live in our Butterfly and Spider Pavilions help keep this exhibit healthy by feeding on organic matter in the soil, like fallen leaves and dead insects. They are nature’s clean up crew!

Catherine Fox

Due to the significant environmental role of roly-polies, they are considered an important biological indicator. Their sensitivity to environmental changes allows them to provide important information about the health of their ecosystem. In other words, wherever you find roly-polies in soil, like these in the Museum's Bugtopia exhibit, you’ve got a healthy habitat. So go dig in the dirt a little and find some roly-polies in your neighborhood!

1 of 1

The Museum’s Bugtopia exhibit houses a terrarium of about 50 common roly-polies. These little critters grow to be about 0.4 inches (10 mm) in length and weigh less than an ounce (0.12 g)! On average, roly-polies live up to 1.5 years. You’ll have to look hard to find all of them, as they are excellent at hiding under debris and camouflaging in their environment.

Catherine Fox

Roly-polies are a type of terrestrial crustacean known as an Isopod, meaning they have multiple pairs of identical-shaped legs. Like all crustaceans (think crabs and lobsters), roly-polies have a tough outer exoskeleton that protects their thinner, more vulnerable underbelly and 14 little legs. This preserved pill-bug specimen (Armadillium spp.) from the Museum's Living Collections allows you to easily count all seven pairs of legs.

Lisa Gonzalez

Roly-polies have a series of overlapping plates, visible here, in their tough exoskeleton that give their body more flexibility. This feature allows them to roll into a protective ball in order to defend themselves against predators.

Franco Folini, Wikimedia Commons

Today, roly-polies can be found worldwide in moist temperate climates; however, they were originally native to the Mediterranean. They are so successful at adapting to terrestrial ecosystems that they can be found almost anywhere there is soft, damp soil. Because they're so easy to find, many young bug enthusiasts first start observing bugs thanks to how cute and gentle roly-polies are!

Franco Folini, Wikimedia Commons

This hard outer exoskeleton, along with a fairly bitter taste, helps protect roly-polies from most predators. But there is one predator they have a hard time escaping from: the roly-poly killer (or woodlouse killer) spider, pictured here. This spider (Dysdera crocata) evolved alongside roly-polies in the same environment; as such, they became specialized predators that have enlarged chelicerae (clasper-like jaws) perfect for piercing through the hard exoskeleton of their prey…like roly-polies. These spiders are ambush predators, hiding in the leaf litter and under rocks to sneak up on roly-polies passing by.

Michel Vuijlsteke, Wikipedia

The Museum's roly-polies can eat pretty much any organic matter (microorganisms and detritus) they find in the dirt, as long as the soil biome has leaf litter and fungus. Roly-polies are important detritivores: animals that eat dead and decaying organisms such as leaf litter, fungus, and animal poop. Detritivores improve soil quality by recycling nutrients back into the soil.

Catherine Fox

Roly-polies have such a positive effect on their ecosystem that the Museum's Living Collections use them in their bioactive (living) terrariums to break down matter and enrich the soil. Bioactive terrariums are ones where different organisms are added to the soil to mimic what naturally happens in the outdoors. Along with springtails, other isopods, and mycelium fungus, roly-polies help the Museum maintain the health of its Living Collections. Roly-polies live alongside the Museum’s stick bugs—like the Malaysian jungle nymph (Heteropteryx dilatata) pictured here—snakes, and skinks to feed off of the larger animals' droppings and clean the enclosure. Roly-polies that live in our Butterfly and Spider Pavilions help keep this exhibit healthy by feeding on organic matter in the soil, like fallen leaves and dead insects. They are nature’s clean up crew!

Lisa Gonzalez

Due to the significant environmental role of roly-polies, they are considered an important biological indicator. Their sensitivity to environmental changes allows them to provide important information about the health of their ecosystem. In other words, wherever you find roly-polies in soil, like these in the Museum's Bugtopia exhibit, you’ve got a healthy habitat. So go dig in the dirt a little and find some roly-polies in your neighborhood!

Catherine Fox

Wheel shells get their name from their slightly compressed shape and decorative marks that look like a spoked wheel. The Museum's Zethalia zeylandica (Hombron & Jacquinot, 1848) specimens were collected in 1996 from Aotea Harbor, Waikato Region in New Zealand by Invertebrate Paleontology Curator Austin Hendy.

Nichols Brown

Wheel shells (Zethalia zelandica) are a species of sea snail, or marine gastropod, in the top snail family Trochidae. Top snails get their common name due to the resemblance of their shells to spinning top toys. This array of the Museum's collection of wheel shells illustrates the variety of color morphs or variation in body color within the species.

Javier Carlos Couper, iNaturalist

Unlike other more herbivorous top snails, wheel shell snails are predominantly filter feeders. By secreting a chain of mucus bubbles, like a sticky net, the snail traps microscopic particles of food (organic debris and detritus) that get reeled in and slurped up.

Javier Carlos Couper, iNaturalist

Wheel shells are small snails that range in size from about 0.5 in to 1.0 in (10 mm to 27 mm) and can be found off the shores of New Zealand - like this one, washed ashore in Auckland that clearly displays the ‘wheel spoke’ pattern that gives this species its common name.

Saryu Mae, iNaturalist

Wheel shells are smooth and shiny spirals that vary in color between shades of yellow and pink, with brown and red streaks. Their color variations help them to blend in with their surroundings.

Nichols Brown

Wheel snails live in the wave zone (10-16 ft or 3-5 m from the water line) off slightly protected sand beaches. You can find them buried in the sand on exposed ocean beaches or washed up after heavy wave action from storms. Empty shells washed ashore are often worn down by sand and wave action, which can reveal the pearlized layers underneath—as seen in these specimens from the Museum's Malacology collection.

1 of 1

Wheel shells (Zethalia zelandica) are a species of sea snail, or marine gastropod, in the top snail family Trochidae. Top snails get their common name due to the resemblance of their shells to spinning top toys. This array of the Museum's collection of wheel shells illustrates the variety of color morphs or variation in body color within the species.

Nichols Brown

Unlike other more herbivorous top snails, wheel shell snails are predominantly filter feeders. By secreting a chain of mucus bubbles, like a sticky net, the snail traps microscopic particles of food (organic debris and detritus) that get reeled in and slurped up.

Javier Carlos Couper, iNaturalist

Wheel shells are small snails that range in size from about 0.5 in to 1.0 in (10 mm to 27 mm) and can be found off the shores of New Zealand - like this one, washed ashore in Auckland that clearly displays the ‘wheel spoke’ pattern that gives this species its common name.

Javier Carlos Couper, iNaturalist

Wheel shells are smooth and shiny spirals that vary in color between shades of yellow and pink, with brown and red streaks. Their color variations help them to blend in with their surroundings.

Saryu Mae, iNaturalist

Wheel snails live in the wave zone (10-16 ft or 3-5 m from the water line) off slightly protected sand beaches. You can find them buried in the sand on exposed ocean beaches or washed up after heavy wave action from storms. Empty shells washed ashore are often worn down by sand and wave action, which can reveal the pearlized layers underneath—as seen in these specimens from the Museum's Malacology collection.

Nichols Brown

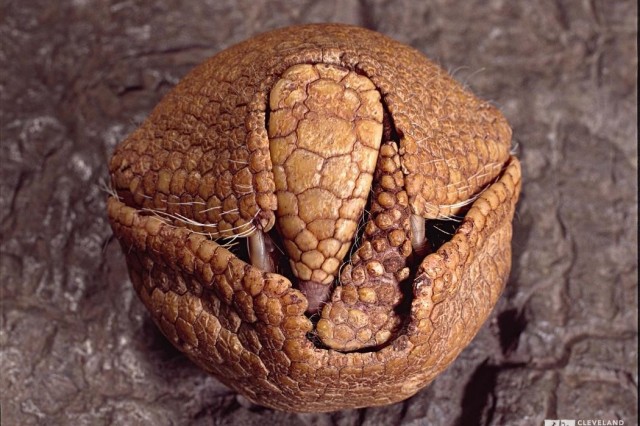

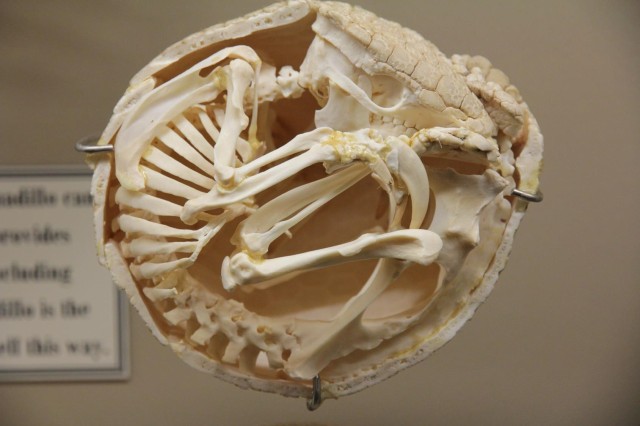

The southern three-banded armadillo (Tolypeutes matacus), so named for the three overlapping bands across its back, is one of only two species of armadillos—the other being the Brazilian three-banded armadillo (Tolypeutes tricinctus)—that can roll itself into a wheel-like ball to protect against predators.

Catherine Fox

Three banded-armadillos (NHM Specimen No.27349) are smaller than most other species of armadillo, with a full body length, from nose to tail, of 11 to 13.8 inches (28-35 cm), weighing between 2.2 and 3.5 pounds (1-1.6 kg). Their lifespan is typically 15-20 years.

Guillermo Menéndez, iNaturalist

Native to the central region of South America, three-banded armadillos live in open forest, grassland, and marsh habitats extending across parts of northern Argentina, southwestern Brazil, Paraguay and Bolivia. These armadillos are solitary creatures that live in dens formed under dense vegetation or in abandoned burrows they find underground.

Cleveland Metroparks Zoo

The animal’s carapace (protective outer covering) is made of keratin, the same tough, versatile material that makes up our hair and fingernails. The three segmented bands across its back allow flexibility of such a tough outer ‘shell’.

Polyoutis, Wikimedia Commons

The armadillo’s thick, leathery body armor is quite roomy underneath, allowing the animal to pull its entire body inside and curl up into a tight ball. The armadillo’s triangular head and tail fold together, sealing the animal safely inside. The armadillo’s steel-trap of a shell isn’t just used for defense. It’s also quite efficient at trapping air and body heat, helping the animal stay warm on cool nights.

FrenchAvatar, Wikipedia

This defensive behavior and hard outer shell are so protective, the only predators with jaws strong enough to break through it are those with tremendous bite power, such as jaguars and pumas.

Nicolas Olejnik, iNaturalist

The southern three-banded armadillo is a nocturnal insectivore, hunting insects - mostly ants and termites - at night. Using its strong legs and large claws, the armadillo digs in the ground or pulls off tree bark to find its food, lapping up the tasty insects with its long, sticky, straw-like tongue.

Rodrigo Tinoco

Three-banded armadillos are considered Near Threatened on the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species. Their conservation is vulnerable to overhunting for food, capture for the pet trade, and habitat destruction to build farmland

1 of 1

Three banded-armadillos (NHM Specimen No.27349) are smaller than most other species of armadillo, with a full body length, from nose to tail, of 11 to 13.8 inches (28-35 cm), weighing between 2.2 and 3.5 pounds (1-1.6 kg). Their lifespan is typically 15-20 years.

Catherine Fox

Native to the central region of South America, three-banded armadillos live in open forest, grassland, and marsh habitats extending across parts of northern Argentina, southwestern Brazil, Paraguay and Bolivia. These armadillos are solitary creatures that live in dens formed under dense vegetation or in abandoned burrows they find underground.

Guillermo Menéndez, iNaturalist

The animal’s carapace (protective outer covering) is made of keratin, the same tough, versatile material that makes up our hair and fingernails. The three segmented bands across its back allow flexibility of such a tough outer ‘shell’.

Cleveland Metroparks Zoo

The armadillo’s thick, leathery body armor is quite roomy underneath, allowing the animal to pull its entire body inside and curl up into a tight ball. The armadillo’s triangular head and tail fold together, sealing the animal safely inside. The armadillo’s steel-trap of a shell isn’t just used for defense. It’s also quite efficient at trapping air and body heat, helping the animal stay warm on cool nights.

Polyoutis, Wikimedia Commons

This defensive behavior and hard outer shell are so protective, the only predators with jaws strong enough to break through it are those with tremendous bite power, such as jaguars and pumas.

FrenchAvatar, Wikipedia

The southern three-banded armadillo is a nocturnal insectivore, hunting insects - mostly ants and termites - at night. Using its strong legs and large claws, the armadillo digs in the ground or pulls off tree bark to find its food, lapping up the tasty insects with its long, sticky, straw-like tongue.

Nicolas Olejnik, iNaturalist

Three-banded armadillos are considered Near Threatened on the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species. Their conservation is vulnerable to overhunting for food, capture for the pet trade, and habitat destruction to build farmland

Rodrigo Tinoco

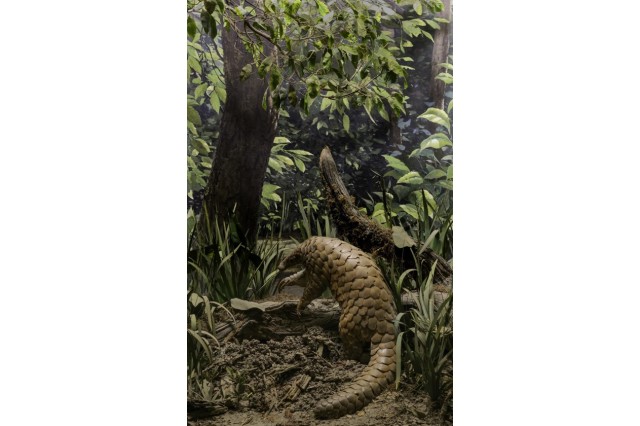

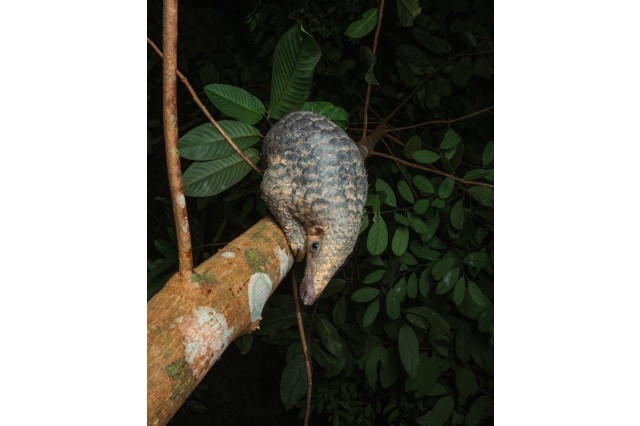

The English name "pangolin" comes from the Malay word pengguling, which means "one who rolls up." When threatened, pangolins roll into a protective ball, using their thick skin and hard, overlapping scales as a tough suit of armor. When a mother pangolin feels threatened, she will surround her small baby (known as a pangopup!) and roll it up within her defensive ball of a body.

Natalja Kent

The African ground pangolin in the Museum's Reframing Diorama exhibit depicts a riverine forest in western Uganda, East Africa at nightfall. This animal was collected by the 1963 Knudsen-Machris East African Expedition.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Beyond rolling into a ball, an ability known as volvation, pangolins have additional defense mechanisms. They can use muscles under their skin to move their sharp scales back and forth, creating a slicing, cutting-like motion. Pangolins can also emit a noxious-smelling chemical from their anal glands, similar to skunks, that deters predators such as leopards and hyenas.

Catherine Fox

Pangolins are unique among mammals in that they are the only mammal completely covered in large, overlapping scales, like those pictured here (NHM Specimen No. 53513), made of keratin - the same material that makes up our hair and fingernails.

iStock

As nocturnal predators, pangolins have small eyes and poor eyesight but an excellent sense of smell to sniff out insects in the dark. Pangolins play a key ecosystem role as voracious insect eaters. It is estimated that a single adult pangolin can eat up to 70 million insects a year!

Yon-lu, Goh, iNaturalist

There are eight species of pangolins, also known as scaly anteaters, that inhabit woodland and savannah habitats across Sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia. Depending on the species, pangolins may have either an arboreal or terrestrial lifestyle. Tree-dwelling pangolins—like this Sunda pangolin—live in hollow trees, while ground-dwelling species nest in deep underground burrows.

Sophie Mowles, iNaturalist

Climbing and burrowing are enabled by strong, powerful forelegs with large, curved claws that cling to trees and dig in soil extremely well. Scientists have discovered extensive pangolin burrows with circular chambers large enough for a human to stand up in!

Catherine Fox

The tree pangolin (Phataginus tricuspis), like this one from the Museum's Mammalogy collection (NHM Specimen No. 53513), uses a semi-prehensile tail—capable of grasping and holding things—for balance while climbing trees. The tree pangolin can also swim! By inhaling a stomach full of air, the animal can increase its buoyancy (like a floatie) to better cross bodies of water.

Justin Hofman

Pangolins are toothless, nocturnal insectivores that feed on ants and termites, which they slurp up using a long, sticky tongue. This feeding behavior known as myrmecophagy—what a fun word! In some species of pangolin, the full length of the tongue is longer than the animal's body! Without teeth, pangolins use small stones and sand ingested with their food to help grind up insects in a gizzard-like stomach.

Russell Gray, iNaturalist

All eight species of pangolins are considered Threatened by the IUCN, vulnerable to overhunting for their meat and scales, deforestation of their natural habitat, and poaching for the exotic pet trade. While pangolins are protected under international law, they have become the most trafficked mammal in the world. Thanks to its strong conservation laws and wildlife rehabilitation centers, Taiwan has the largest population of pangolins around the world. The establishment of World Pangolin Day on the third Saturday of February has also helped raise awareness about this extraordinary animal in need of our protection.

1 of 1

The African ground pangolin in the Museum's Reframing Diorama exhibit depicts a riverine forest in western Uganda, East Africa at nightfall. This animal was collected by the 1963 Knudsen-Machris East African Expedition.

Natalja Kent

Beyond rolling into a ball, an ability known as volvation, pangolins have additional defense mechanisms. They can use muscles under their skin to move their sharp scales back and forth, creating a slicing, cutting-like motion. Pangolins can also emit a noxious-smelling chemical from their anal glands, similar to skunks, that deters predators such as leopards and hyenas.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Pangolins are unique among mammals in that they are the only mammal completely covered in large, overlapping scales, like those pictured here (NHM Specimen No. 53513), made of keratin - the same material that makes up our hair and fingernails.

Catherine Fox

As nocturnal predators, pangolins have small eyes and poor eyesight but an excellent sense of smell to sniff out insects in the dark. Pangolins play a key ecosystem role as voracious insect eaters. It is estimated that a single adult pangolin can eat up to 70 million insects a year!

iStock

There are eight species of pangolins, also known as scaly anteaters, that inhabit woodland and savannah habitats across Sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia. Depending on the species, pangolins may have either an arboreal or terrestrial lifestyle. Tree-dwelling pangolins—like this Sunda pangolin—live in hollow trees, while ground-dwelling species nest in deep underground burrows.

Yon-lu, Goh, iNaturalist

Climbing and burrowing are enabled by strong, powerful forelegs with large, curved claws that cling to trees and dig in soil extremely well. Scientists have discovered extensive pangolin burrows with circular chambers large enough for a human to stand up in!

Sophie Mowles, iNaturalist

The tree pangolin (Phataginus tricuspis), like this one from the Museum's Mammalogy collection (NHM Specimen No. 53513), uses a semi-prehensile tail—capable of grasping and holding things—for balance while climbing trees. The tree pangolin can also swim! By inhaling a stomach full of air, the animal can increase its buoyancy (like a floatie) to better cross bodies of water.

Catherine Fox

Pangolins are toothless, nocturnal insectivores that feed on ants and termites, which they slurp up using a long, sticky tongue. This feeding behavior known as myrmecophagy—what a fun word! In some species of pangolin, the full length of the tongue is longer than the animal's body! Without teeth, pangolins use small stones and sand ingested with their food to help grind up insects in a gizzard-like stomach.

Justin Hofman

All eight species of pangolins are considered Threatened by the IUCN, vulnerable to overhunting for their meat and scales, deforestation of their natural habitat, and poaching for the exotic pet trade. While pangolins are protected under international law, they have become the most trafficked mammal in the world. Thanks to its strong conservation laws and wildlife rehabilitation centers, Taiwan has the largest population of pangolins around the world. The establishment of World Pangolin Day on the third Saturday of February has also helped raise awareness about this extraordinary animal in need of our protection.

Russell Gray, iNaturalist

Step into California’s past, and you’ll find the humble ox cart, or carreta, playing a starring role in the daily lives of Californians across the centuries. These sturdy, two-wheeled, wooden carts, pulled by the steady strength of oxen, helped shape the state’s history from the time of Spanish rancheros in the late 1700s to American settlers moving westward across the California trail a century later.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, History (Material Culture)

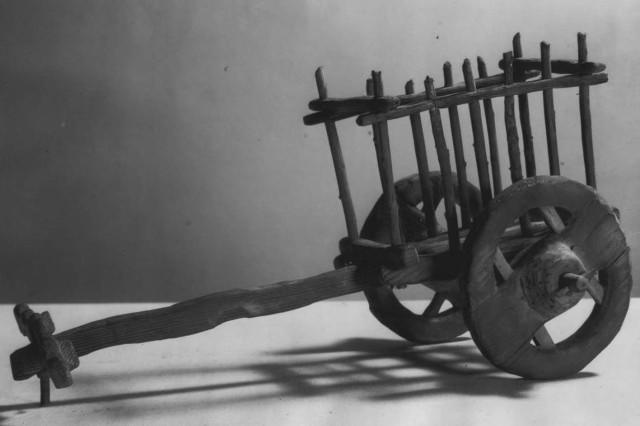

To better traverse the rough California roads of the 18th and 19th centuries, solid wheels with wide treads—often made from a single side of a tree trunk—were more secure and reliable for hauling heavy goods than slender spoked-wheels. This carreta in the Museum's History Department's Material Culture collection dates back to the 1800s.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

California carretas had large, solid wood wheels with straight yokes that lashed onto either the horns or shoulders of the oxen. Oxen tend to be slower than horses or mules but were preferred when hauling heavy loads long distances thanks to their increased strength, calm demeaners, and ability to survive on scant resources.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

Carretas were more than just transportation; they were lifelines. Hauling trade goods, agricultural products, personal property, and even people—like these two women in front of an adobe—these ox carts connected communities and powered the labor that built California.

1 of 1

To better traverse the rough California roads of the 18th and 19th centuries, solid wheels with wide treads—often made from a single side of a tree trunk—were more secure and reliable for hauling heavy goods than slender spoked-wheels. This carreta in the Museum's History Department's Material Culture collection dates back to the 1800s.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, History (Material Culture)

California carretas had large, solid wood wheels with straight yokes that lashed onto either the horns or shoulders of the oxen. Oxen tend to be slower than horses or mules but were preferred when hauling heavy loads long distances thanks to their increased strength, calm demeaners, and ability to survive on scant resources.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

Carretas were more than just transportation; they were lifelines. Hauling trade goods, agricultural products, personal property, and even people—like these two women in front of an adobe—these ox carts connected communities and powered the labor that built California.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

Wagons played a critical role in shaping the early history of California and, by extension, the American West. These wagons, though humble, were transformative tools that made the grueling journey possible. The first wagon train of Anglo settlers arrived in California in 1841, crossing the formidable Sierra Nevada via the California Trail.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, History (Material Culture)

The wagon wheels that rolled into California—one of which is on display in the Museum's Becoming Los Angeles exhibit—brought not only people but also the dreams and determination that helped shape the Golden State. These covered wagons were more than just transportation—they were rolling homes, shelters, and symbols of hope for families chasing new beginnings and new fortunes in the American West.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

Wagons played a critical role in shaping the early history of California and, by extension, the American West. In 1905, these men used horse-drawn wagons to clear a site at Main Street and Commercial Street for the new Federal Building. These wagons, though humble, were transformative tools that made the grueling work of building a modern Los Angeles possible.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

Chuck-wagons, like this one from the 1890s, were lifelines that cowboys and vaqueros depended on to carry supplies and provide shelter over long distances. The spoked wheels and lightweight design of these wagons made it possible to navigate rough, rocky terrain.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

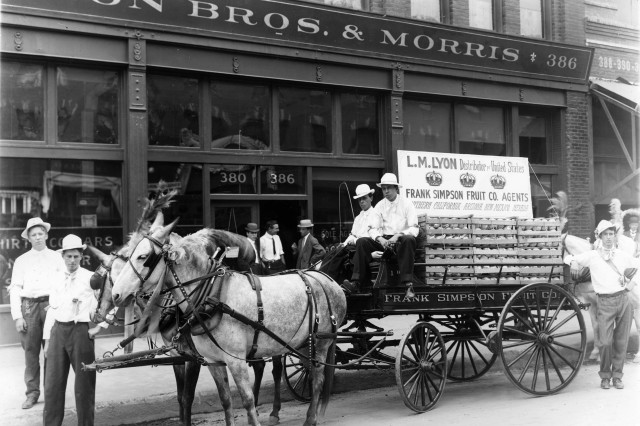

In the late 19th century, California’s agricultural landscape underwent a dramatic shift. What began as sprawling ranches and vast fields of grain evolved into smaller, more focused farms specializing in fruit cultivation. This early 20th century photograph, taken at the corner of Los Angeles Street, north of Fifth Street, illustrates how the Frank Simpson Fruit Company used wagons to deliver and advertise its goods around town.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

By 1910, the value of intensive crops like grapes, citrus, and deciduous fruits matched that of traditional extensive crops, positioning California as a global agricultural powerhouse. In this photograph, Redlands Orange Growers Association workers load open-topped crates of oranges in a horse-drawn wagon.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

To cross wide or fast-moving rivers, wagons were often dismantled and floated across. Unfortunately, that tactic was not used by Adam Clark Vroman party whose horse-drawn wagon got stuck in a muddy creek while traveling in 1895 from Los Angeles to the Hopi Pueblo in Arizona. Vroman was a photographer famous for capturing Southwestern landscapes and images of Hopi and Zuni Tribe culture between 1895 and 1904. A resident of Pasadena, Adam Clark Vroman founded Vroman’s Bookstore in 1894—California's oldest independent bookstore still in operation today!

1 of 1

The wagon wheels that rolled into California—one of which is on display in the Museum's Becoming Los Angeles exhibit—brought not only people but also the dreams and determination that helped shape the Golden State. These covered wagons were more than just transportation—they were rolling homes, shelters, and symbols of hope for families chasing new beginnings and new fortunes in the American West.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, History (Material Culture)

Wagons played a critical role in shaping the early history of California and, by extension, the American West. In 1905, these men used horse-drawn wagons to clear a site at Main Street and Commercial Street for the new Federal Building. These wagons, though humble, were transformative tools that made the grueling work of building a modern Los Angeles possible.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

Chuck-wagons, like this one from the 1890s, were lifelines that cowboys and vaqueros depended on to carry supplies and provide shelter over long distances. The spoked wheels and lightweight design of these wagons made it possible to navigate rough, rocky terrain.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

In the late 19th century, California’s agricultural landscape underwent a dramatic shift. What began as sprawling ranches and vast fields of grain evolved into smaller, more focused farms specializing in fruit cultivation. This early 20th century photograph, taken at the corner of Los Angeles Street, north of Fifth Street, illustrates how the Frank Simpson Fruit Company used wagons to deliver and advertise its goods around town.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

By 1910, the value of intensive crops like grapes, citrus, and deciduous fruits matched that of traditional extensive crops, positioning California as a global agricultural powerhouse. In this photograph, Redlands Orange Growers Association workers load open-topped crates of oranges in a horse-drawn wagon.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

To cross wide or fast-moving rivers, wagons were often dismantled and floated across. Unfortunately, that tactic was not used by Adam Clark Vroman party whose horse-drawn wagon got stuck in a muddy creek while traveling in 1895 from Los Angeles to the Hopi Pueblo in Arizona. Vroman was a photographer famous for capturing Southwestern landscapes and images of Hopi and Zuni Tribe culture between 1895 and 1904. A resident of Pasadena, Adam Clark Vroman founded Vroman’s Bookstore in 1894—California's oldest independent bookstore still in operation today!

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

In the early days of transportation in Los Angeles, the streets bustled with the sounds of hooves and wooden wheels. From its origins as a 16th century Spanish frontier outpost, Los Angeles relied on animal-powered vehicles to move goods and people. The humble carreta and horse-drawn wagon, paved the way for later innovations like stagecoaches and carriages.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, History (Material Culture)

In 1894, the Banning Brothers began offering $1 stagecoach tours of Santa Catalina Island, marking the beginning of its rise as a tourist destination. One of their stagecoaches is preserved in the Museum’s History Department Material Culture collection, reflecting this important chapter in the island’s history.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

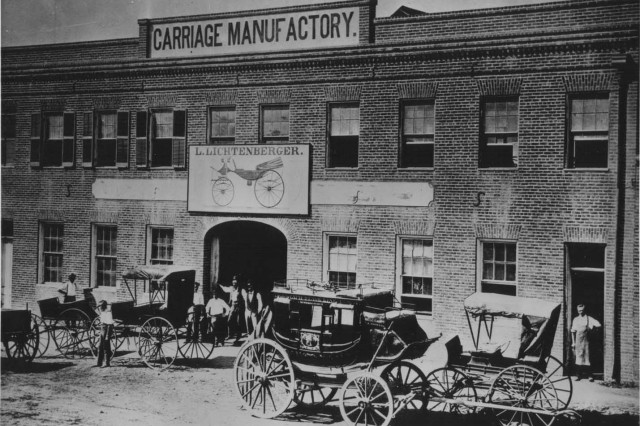

In the 1870s, public transportation was virtually nonexistent, as Los Angeles was still small enough to navigate on foot. But as the city expanded, regular wheeled transport became essential. The Telegraph Stage Line (a stagecoach route that ran alongside a telegraph line) that ran between Los Angeles and San Francisco in the 1870s passed in front of L. Lichtenberger Carriage Manufactory, pictured here. This warehouse was located on the west side of Spring Street just south of First Street in Los Angeles—across the street from where L.A. City Hall is located today.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

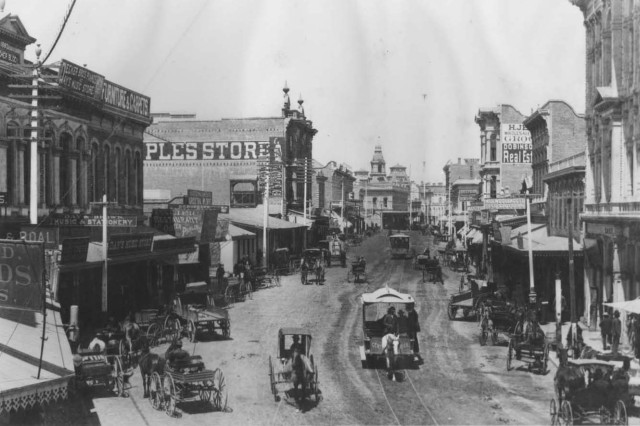

Even in 1887, the corner of Fourth and Spring Streets in Downtown Los Angeles was a bustling hub of commercial activity. Oddly enough, city leaders didn’t officially ban horses from downtown streets until 1924, a rule that remains in effect even today.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

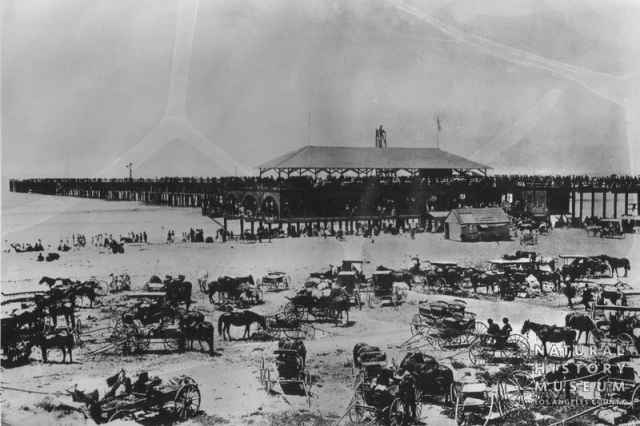

By 1900, there was one horse for every 12.7 residents—a whopping 8,065 horses working hard in a rapidly growing metropolis. In this 1902 photograph, many beachgoers traveled to Long Beach in their horse-drawn carriages to enjoy a relaxing day a the beach.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

In this photograph, taken sometime between 1903-1905, The Carriage Shop at 709 South Olive Street run by Arthur R. Scott was one of many carriage repair shops and blacksmiths that continued to service Los Angeles' horse-drawn vehicles well into the 1920s.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

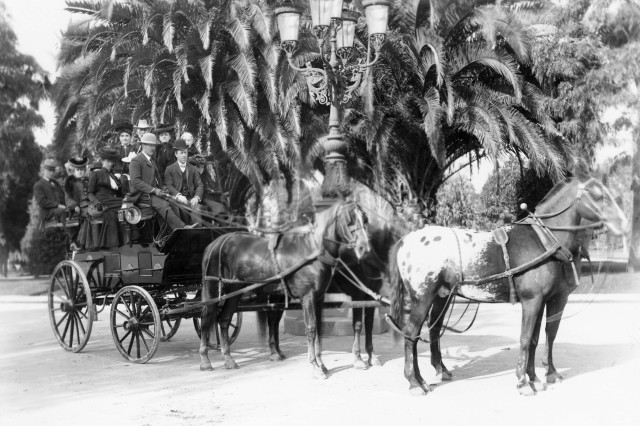

One charming example of city carriages was the "tally-ho" horse-drawn carriage. Popular for sightseeing, this open coach with no roof or sides offered riders a picturesque way to take in the scenery—whether in bustling cities or the quiet countryside. At the turn of the century, Los Angeles's parks hosted a popular tally-ho touring industry for well-to-do Angelenos, like this one parked at Saint James Park in 1900.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

Oddly enough, horses weren't the only animal-powered vehicles found on L.A. streets. In the early 1900s, Lincoln Park (at Hills St. and 5th St—today's Pershing Square) was home to the Los Angeles Ostrich Farm, where customers could buy ostrich eggs and feathers, or even take an ostrich-powered joy ride! Ostriches were bred for exhibition, spectator races, and trained to pull visitors by cart—like this one from 1928. Visit our Becoming Los Angeles exhibit to see how large an ostrich egg actually is!

1 of 1

In 1894, the Banning Brothers began offering $1 stagecoach tours of Santa Catalina Island, marking the beginning of its rise as a tourist destination. One of their stagecoaches is preserved in the Museum’s History Department Material Culture collection, reflecting this important chapter in the island’s history.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, History (Material Culture)

In the 1870s, public transportation was virtually nonexistent, as Los Angeles was still small enough to navigate on foot. But as the city expanded, regular wheeled transport became essential. The Telegraph Stage Line (a stagecoach route that ran alongside a telegraph line) that ran between Los Angeles and San Francisco in the 1870s passed in front of L. Lichtenberger Carriage Manufactory, pictured here. This warehouse was located on the west side of Spring Street just south of First Street in Los Angeles—across the street from where L.A. City Hall is located today.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

Even in 1887, the corner of Fourth and Spring Streets in Downtown Los Angeles was a bustling hub of commercial activity. Oddly enough, city leaders didn’t officially ban horses from downtown streets until 1924, a rule that remains in effect even today.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

By 1900, there was one horse for every 12.7 residents—a whopping 8,065 horses working hard in a rapidly growing metropolis. In this 1902 photograph, many beachgoers traveled to Long Beach in their horse-drawn carriages to enjoy a relaxing day a the beach.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

In this photograph, taken sometime between 1903-1905, The Carriage Shop at 709 South Olive Street run by Arthur R. Scott was one of many carriage repair shops and blacksmiths that continued to service Los Angeles' horse-drawn vehicles well into the 1920s.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

One charming example of city carriages was the "tally-ho" horse-drawn carriage. Popular for sightseeing, this open coach with no roof or sides offered riders a picturesque way to take in the scenery—whether in bustling cities or the quiet countryside. At the turn of the century, Los Angeles's parks hosted a popular tally-ho touring industry for well-to-do Angelenos, like this one parked at Saint James Park in 1900.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

Oddly enough, horses weren't the only animal-powered vehicles found on L.A. streets. In the early 1900s, Lincoln Park (at Hills St. and 5th St—today's Pershing Square) was home to the Los Angeles Ostrich Farm, where customers could buy ostrich eggs and feathers, or even take an ostrich-powered joy ride! Ostriches were bred for exhibition, spectator races, and trained to pull visitors by cart—like this one from 1928. Visit our Becoming Los Angeles exhibit to see how large an ostrich egg actually is!

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

Motorized or horseless carriages came on the scene in 1830s Europe when a battery was used to replace the horsepower of…well, horses! While these early electric cars were undoubtedly an engineering feat with the potential to change the world of transportation, they started out as mere novelty items until rechargeable batteries were invented in 1859. Motorized carriages started to take off in the U.S. after William Morrison from Des Moines, Iowa patented his “electric carriage” in 1890. This front-wheel drive, four-horsepower, vehicle with 24 battery cells could get 50 miles to the charge and reach top speeds of less than 20 mph!

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, History (Material Culture)

Los Angeles’ love affair with the automobile began with the Tourist, the first production car manufactured on the West Coast! Built in 1902 by the Auto Vehicle Company in downtown Los Angeles, the Tourist became California’s best-selling car before World War I. Today, the Tourist car on display in the Natural History Museum's (NHM) Becoming Los Angeles exhibit is the earliest surviving example of this historic vehicle. The rise of the Tourist wasn’t just about personal transportation—it symbolized a shift in Los Angeles itself. Fueled by the region’s booming oil industry, the automobile era contributed to the decline of early electric cars and helped shape the sprawling, car-centered city we know today!

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

These two Angelenos traveling through town in 1911 are driving in a steam-powered car. Steam cars were powered by an external combustion engine that used steam pressure to push the pistons back and forth inside the cylinders, creating the rotational force needed to get the car in motion. Steam-powered cars dominated the personal vehicle market from the 1890s to 1910s; they produced much lower emissions than gasoline-powered vehicles—though with lower thermal efficiency—and had a much farther range than electric vehicles. However, they couldn't compete for long with the mass production of cheaper, more reliable internal combustion engines of the Ford Model T.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

By 1900, electric taxis were commonplace in big cities and wealthy urban homes that were newly wired for electricity, as depicted in this 1903 image of a line of parked cars along Broadway between 6th St. and 7th St. in Los Angeles. Motorized carriages were cleaner, quieter, more dependable, and easier to drive than horse-drawn carriages—perfect for promenading along city streets. However, their overall range on a single charge, slow speed, and inaccessibility to un-electrified rural areas, couldn’t compete with the cheaper, faster, more reliable, internal combustion engines rolling off Henry Ford’s assembly line in the 1910s. By the 1920s, electric motorized carriages were replaced by gas-powered vehicles—paving the way for the modern car culture of the 20th century.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

Who doesn't love a parade? In the early 20th century, as horse-drawn carriages faded from city streets, even parade floats switched to electric vehicles. Between 1894 and 1916, Los Angeles held a multiday, multiethnic festival celebrating the history of California known as La Fiesta de Los Angeles. As California-themed floats—such as this 1908 floral arrangement on wheels—paraded through Downtown Los Angeles from the Old Plaza to Fiesta Park (today's El Pueblo de Los Ángeles Historical Monument to the intersection of Grand Ave. and 12th St.).

1 of 1

Los Angeles’ love affair with the automobile began with the Tourist, the first production car manufactured on the West Coast! Built in 1902 by the Auto Vehicle Company in downtown Los Angeles, the Tourist became California’s best-selling car before World War I. Today, the Tourist car on display in the Natural History Museum's (NHM) Becoming Los Angeles exhibit is the earliest surviving example of this historic vehicle. The rise of the Tourist wasn’t just about personal transportation—it symbolized a shift in Los Angeles itself. Fueled by the region’s booming oil industry, the automobile era contributed to the decline of early electric cars and helped shape the sprawling, car-centered city we know today!

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, History (Material Culture)

These two Angelenos traveling through town in 1911 are driving in a steam-powered car. Steam cars were powered by an external combustion engine that used steam pressure to push the pistons back and forth inside the cylinders, creating the rotational force needed to get the car in motion. Steam-powered cars dominated the personal vehicle market from the 1890s to 1910s; they produced much lower emissions than gasoline-powered vehicles—though with lower thermal efficiency—and had a much farther range than electric vehicles. However, they couldn't compete for long with the mass production of cheaper, more reliable internal combustion engines of the Ford Model T.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

By 1900, electric taxis were commonplace in big cities and wealthy urban homes that were newly wired for electricity, as depicted in this 1903 image of a line of parked cars along Broadway between 6th St. and 7th St. in Los Angeles. Motorized carriages were cleaner, quieter, more dependable, and easier to drive than horse-drawn carriages—perfect for promenading along city streets. However, their overall range on a single charge, slow speed, and inaccessibility to un-electrified rural areas, couldn’t compete with the cheaper, faster, more reliable, internal combustion engines rolling off Henry Ford’s assembly line in the 1910s. By the 1920s, electric motorized carriages were replaced by gas-powered vehicles—paving the way for the modern car culture of the 20th century.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

Who doesn't love a parade? In the early 20th century, as horse-drawn carriages faded from city streets, even parade floats switched to electric vehicles. Between 1894 and 1916, Los Angeles held a multiday, multiethnic festival celebrating the history of California known as La Fiesta de Los Angeles. As California-themed floats—such as this 1908 floral arrangement on wheels—paraded through Downtown Los Angeles from the Old Plaza to Fiesta Park (today's El Pueblo de Los Ángeles Historical Monument to the intersection of Grand Ave. and 12th St.).

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

Los Angeles and cars go hand in hand—think endless freeways, iconic drives like Mulholland Drive and Sunset Boulevard, and a love for all things fast and flashy. The city’s car obsession revved up in the early 20th century, fueled by its sprawling layout. Post-war, Los Angeles became the birthplace of lowriders, hot rods, and a street-racing scene straight out of the movies. From classic car shows to modern electric vehicles, the city’s automotive love affair keeps evolving. Whether you’re cruising the Pacific Coast Highway or stuck on the 405, in L.A. the car isn’t just transportation—it’s a way of life and a statement of style.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

Los Angeles has always been fast—on freeways, in lifestyles, and especially on the racetrack. The city’s love affair with race car driving goes back to the 1910s, when dirt tracks drew speed-hungry crowds. Legendary venues like the Ascot Park Speedway (which used to be located south of Gardena, CA) hosted adrenaline-fueled battles, putting L.A. at the forefront of the motorsports scene. In this speedy snapshot from 1919, Lambert Hillyer (with Marshall Neilan in the passenger seat) drives the W.S. Hart Studio’s Race Car No. 1 passed the grandstand at Ascot Park at a fund raising event to benefit the Actor's Fund - an organization that still exists today, providing care and services to professionals in the arts.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

Hollywood is synonymous with Los Angeles and cars have played an essential role in films both in front of and behind the camera. In this 1920s photograph of an automobile towing a trailer filled with actors at Universal Pictures Studio the side of the trailer reads: “See America First, Transcontinental Production Unit, Motion Pictures of Representative Cities, of the United States, Originated by Carl Laemmle, President of Universal Pictures, Universal City, California".

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

Pictured here on opening day in December 1924, the famously scenic Mulholland Highway started out as a three lane dirt road. Today, the highway winds about 50 miles through the Santa Monica Mountains from Topanga Canyon in the east to Leo Carillo State Beach in the west.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

Southern California has always been about “the beach life”. Just like today, Angelenos flocked to Downtown Redondo Beach in 1924 to enjoy the sand and surf of a sunny afternoon at the beach and fresh caught seafood.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

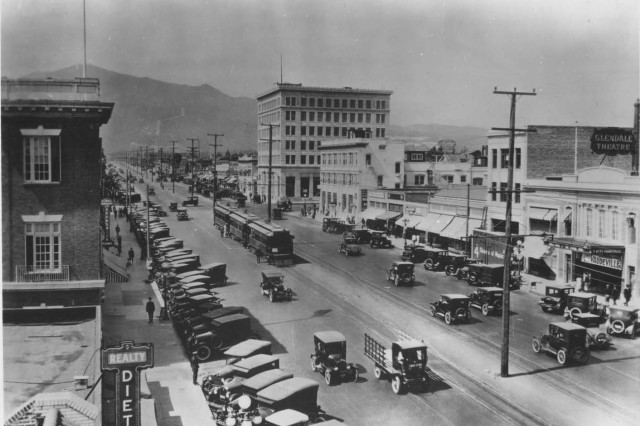

This 1926 rooftop view looking north up Brand Blvd. in Glendale, CA illustrates the hustle and bustle of early car culture in Los Angeles. It’s no surprise parking in Downtown Glendale was just as hard to find in the days of the Model T! Today, the city hopes to bring back the electric streetcar, reconnecting Downtown L.A. to Burbank via Glendale, along some of the same routes as the Pacific Electric Railway (or the "Red Cars") did between 1904 to 1955.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

In drought-prone Los Angeles, where dry brush and high winds can spark chaos in minutes, firefighters are more than first responders—they’re real-life action heroes. From routine medical calls to battling massive wildfires, these men and women embody grit, resilience, and an unshakable sense of duty.

Fire engines have certainly become more advanced and high-tech since this photograph was taken of a fire wagon truck team in 1929, L.A. firefighters have always risen above the flames—literally and figuratively.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

The Los Angeles Auto Show has been an annual fixture in the city since 1907 (except for the ten years surrounding the Second World War. As one of the largest car shows in the United States, the L.A. Auto Show showcases the latest styles, innovations, and futuristic technologies of the auto industry. Just like their counterparts today, these two models did their best to attract spectators to the 1955 L.A. Auto Show at the Pan Pacific Auditorium.

1 of 1

Los Angeles has always been fast—on freeways, in lifestyles, and especially on the racetrack. The city’s love affair with race car driving goes back to the 1910s, when dirt tracks drew speed-hungry crowds. Legendary venues like the Ascot Park Speedway (which used to be located south of Gardena, CA) hosted adrenaline-fueled battles, putting L.A. at the forefront of the motorsports scene. In this speedy snapshot from 1919, Lambert Hillyer (with Marshall Neilan in the passenger seat) drives the W.S. Hart Studio’s Race Car No. 1 passed the grandstand at Ascot Park at a fund raising event to benefit the Actor's Fund - an organization that still exists today, providing care and services to professionals in the arts.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

Hollywood is synonymous with Los Angeles and cars have played an essential role in films both in front of and behind the camera. In this 1920s photograph of an automobile towing a trailer filled with actors at Universal Pictures Studio the side of the trailer reads: “See America First, Transcontinental Production Unit, Motion Pictures of Representative Cities, of the United States, Originated by Carl Laemmle, President of Universal Pictures, Universal City, California".

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

Pictured here on opening day in December 1924, the famously scenic Mulholland Highway started out as a three lane dirt road. Today, the highway winds about 50 miles through the Santa Monica Mountains from Topanga Canyon in the east to Leo Carillo State Beach in the west.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

Southern California has always been about “the beach life”. Just like today, Angelenos flocked to Downtown Redondo Beach in 1924 to enjoy the sand and surf of a sunny afternoon at the beach and fresh caught seafood.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

This 1926 rooftop view looking north up Brand Blvd. in Glendale, CA illustrates the hustle and bustle of early car culture in Los Angeles. It’s no surprise parking in Downtown Glendale was just as hard to find in the days of the Model T! Today, the city hopes to bring back the electric streetcar, reconnecting Downtown L.A. to Burbank via Glendale, along some of the same routes as the Pacific Electric Railway (or the "Red Cars") did between 1904 to 1955.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

In drought-prone Los Angeles, where dry brush and high winds can spark chaos in minutes, firefighters are more than first responders—they’re real-life action heroes. From routine medical calls to battling massive wildfires, these men and women embody grit, resilience, and an unshakable sense of duty.

Fire engines have certainly become more advanced and high-tech since this photograph was taken of a fire wagon truck team in 1929, L.A. firefighters have always risen above the flames—literally and figuratively.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

The Los Angeles Auto Show has been an annual fixture in the city since 1907 (except for the ten years surrounding the Second World War. As one of the largest car shows in the United States, the L.A. Auto Show showcases the latest styles, innovations, and futuristic technologies of the auto industry. Just like their counterparts today, these two models did their best to attract spectators to the 1955 L.A. Auto Show at the Pan Pacific Auditorium.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

The first two-wheeled, man-powered vehicle was a far cry from today's high-end road racing bikes and tricked-out custom motorcycles. The original dandy-horse bicycle was comprised of two wooden, spoked wheels attached to a simple, horizontal frame with a hinged handlebar for steering. In order to power the vehicle, the rider would straddle the bike and push along the ground with their feet (à la The Flintstones). The Museum's History Department contains a vast collection of material culture and ephemera that taps into the diversity and artistry of getting around this vibrant city on two (or even three) wheels.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

The origins of the bicycle date back to 1817, with the German invention by Karl von Drais of the velocipede. The term velocipede now generally refers to any human-powered land vehicle with wheels developed between 1817 and 1880—essentially, all precursors to the modern-day bicycle, as pictured in this studio photograph of a tricycle velocipede.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

This early tandem bicycle, with wooden wheels and a metal frame, was a movie prop in the 1925 silent film Not So Long Ago. This type of bike, with pedals attached directly to the wheel and no shock absorption, were known as "Bone Shakers".

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

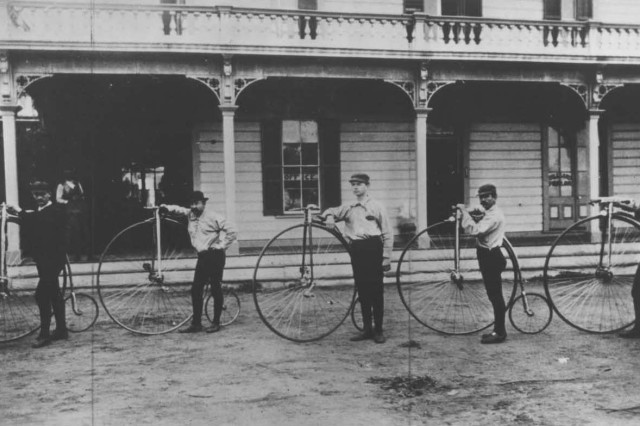

The high wheel or penny-farthing bicycle was the first velocipede to be made completely out of metal, instead of wooden wheels and frames. The “penny-farthing” bicycle earned its British nick-name in the 1890s from its sideways resemblance to a large penny coin (front wheel) sitting next to a much smaller farthing coin (back wheel).

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

This photograph, 1800's bicyclers pose at Agricultural Park, the same site where the Museum, the LA Memorial Coliseum, and Exposition Park occupy on today. The high wheel bicycle may have been a short-lived (if not impractical design) but its legacy as a symbol of Victorian Era high society and the kicking off point for bicycling as a sport still persists today.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

Velocipede clubs for the well-to-do became trendy and indoor riding academies (think giant roller rinks) took off in the 1880s—just like the 1887 Los Angeles Bicycle Champions pictured here (from left to right: Wesley King, Arthur Allen, John Off, L. Kinney). Today, we can attribute many of the innovations used in velocipedes—to make them faster, more agile, even more comfortable—to modern features in automobiles, such as rack and pinion steering, the differential, and band brakes.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

Due to a tall center of gravity and the tendency to fall forward over the handlebars when encountering obstructions in the road (a term known as “taking a header”), the high wheel became obsolete by the 1890s when modern “safety bikes” were introduced. This updated design that we know of as a regular bicycle today, was capable of reaching similar speeds with smaller wheels thanks to its chain-and-gear drive. Safety bikes, pictured here with Los Angeles bicyclists from 1893, took over the market due to the greater ease of mounting and dismounting from smaller wheels that significantly reduced the danger of falling from great heights.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

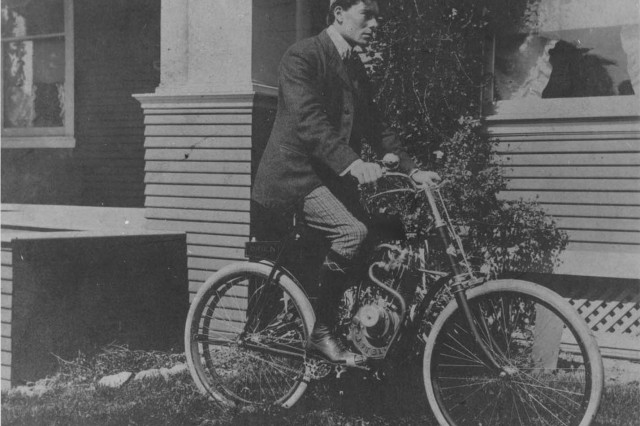

Modeled after the "safety bicycle", the first steam-powered motorcycles appeared in 1860s France. Motorized bicycles (fuel-powered with an internal combustion engine) hit the European market in the 1880s, and by 1898 the first "motorcycle" manufactured in the United States—the Orient-Aster model—was sold in Massachusetts. Famous Los Angeles bicycle racer, race car driver, and later car dealer Ralph Hamlin owned the first motorcycle west of the Rockies—seen here showing off his "Orient" motorcycle in 1901.

1 of 1

The origins of the bicycle date back to 1817, with the German invention by Karl von Drais of the velocipede. The term velocipede now generally refers to any human-powered land vehicle with wheels developed between 1817 and 1880—essentially, all precursors to the modern-day bicycle, as pictured in this studio photograph of a tricycle velocipede.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

This early tandem bicycle, with wooden wheels and a metal frame, was a movie prop in the 1925 silent film Not So Long Ago. This type of bike, with pedals attached directly to the wheel and no shock absorption, were known as "Bone Shakers".

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

The high wheel or penny-farthing bicycle was the first velocipede to be made completely out of metal, instead of wooden wheels and frames. The “penny-farthing” bicycle earned its British nick-name in the 1890s from its sideways resemblance to a large penny coin (front wheel) sitting next to a much smaller farthing coin (back wheel).

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

This photograph, 1800's bicyclers pose at Agricultural Park, the same site where the Museum, the LA Memorial Coliseum, and Exposition Park occupy on today. The high wheel bicycle may have been a short-lived (if not impractical design) but its legacy as a symbol of Victorian Era high society and the kicking off point for bicycling as a sport still persists today.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

Velocipede clubs for the well-to-do became trendy and indoor riding academies (think giant roller rinks) took off in the 1880s—just like the 1887 Los Angeles Bicycle Champions pictured here (from left to right: Wesley King, Arthur Allen, John Off, L. Kinney). Today, we can attribute many of the innovations used in velocipedes—to make them faster, more agile, even more comfortable—to modern features in automobiles, such as rack and pinion steering, the differential, and band brakes.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

Due to a tall center of gravity and the tendency to fall forward over the handlebars when encountering obstructions in the road (a term known as “taking a header”), the high wheel became obsolete by the 1890s when modern “safety bikes” were introduced. This updated design that we know of as a regular bicycle today, was capable of reaching similar speeds with smaller wheels thanks to its chain-and-gear drive. Safety bikes, pictured here with Los Angeles bicyclists from 1893, took over the market due to the greater ease of mounting and dismounting from smaller wheels that significantly reduced the danger of falling from great heights.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

Modeled after the "safety bicycle", the first steam-powered motorcycles appeared in 1860s France. Motorized bicycles (fuel-powered with an internal combustion engine) hit the European market in the 1880s, and by 1898 the first "motorcycle" manufactured in the United States—the Orient-Aster model—was sold in Massachusetts. Famous Los Angeles bicycle racer, race car driver, and later car dealer Ralph Hamlin owned the first motorcycle west of the Rockies—seen here showing off his "Orient" motorcycle in 1901.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

Los Angeles has always been a vibe, and its roller skating culture is no exception. From beachside boardwalks to inner-city parks, skaters have been gliding, grooving, and making statements on wheels since the Los Angeles Thunderbirds roller derby rolled into town in the 1960s. In L.A., roller skating is just as much about style and skill as it is about nostalgia. Whether you’re skating for fitness, fun, or self-expression, one thing’s for sure: there’s no better place to roll than under the California sun.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, History (Material Culture)

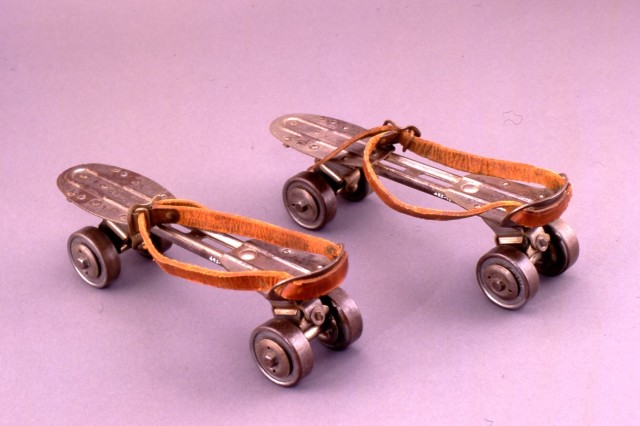

Charlie Chaplin’s film skates from Modern Times (1936) are a piece of cinematic history. Worn in one of the movie’s most daring and hilarious scenes, Chaplin’s Tramp glides near a ledge, balancing tension with hilarity. Now a part of the Museum’s History Department collection, these skates embody Chaplin’s ability to use physical comedy to turn simple props into tools of dynamic humor and brilliant storytelling.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

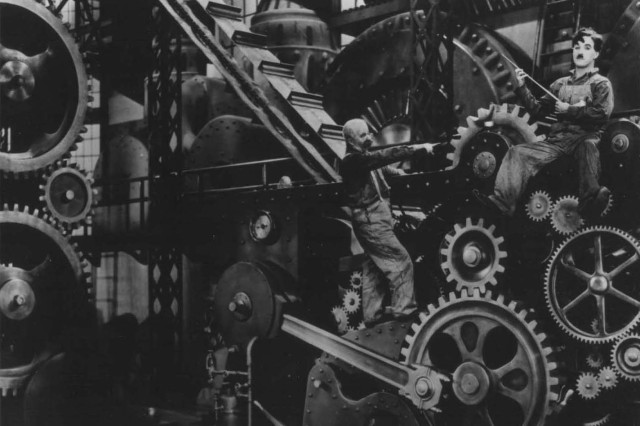

This scene from Charlie Chaplin's silent film Modern Times (1935) depicts the working man's iconic struggle with industrialization. The Tramp gets caught in the cogs of the machine, a comedic yet poignant critique of modern labor at the time.

1 of 1

Charlie Chaplin’s film skates from Modern Times (1936) are a piece of cinematic history. Worn in one of the movie’s most daring and hilarious scenes, Chaplin’s Tramp glides near a ledge, balancing tension with hilarity. Now a part of the Museum’s History Department collection, these skates embody Chaplin’s ability to use physical comedy to turn simple props into tools of dynamic humor and brilliant storytelling.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, History (Material Culture)

This scene from Charlie Chaplin's silent film Modern Times (1935) depicts the working man's iconic struggle with industrialization. The Tramp gets caught in the cogs of the machine, a comedic yet poignant critique of modern labor at the time.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Seaver Center for Western History Research

The Museum’s collection of wheels takes you on a fascinating ride through time, nature, and innovation! These artifacts and stories remind us how wheels, both natural and man-made, have powered progress, shaped cultures, and brought people together. As you explore this dynamic collection, you’ll see that the humble wheel is more than just a tool—it’s a symbol of resilience, creativity, and community. Whether rolling into battle, playing under the California sun, or cruising the Pacific Coast Highway, the wheel continues to propel us forward. We invite you to keep exploring, learning, and celebrating the history that keeps us moving.