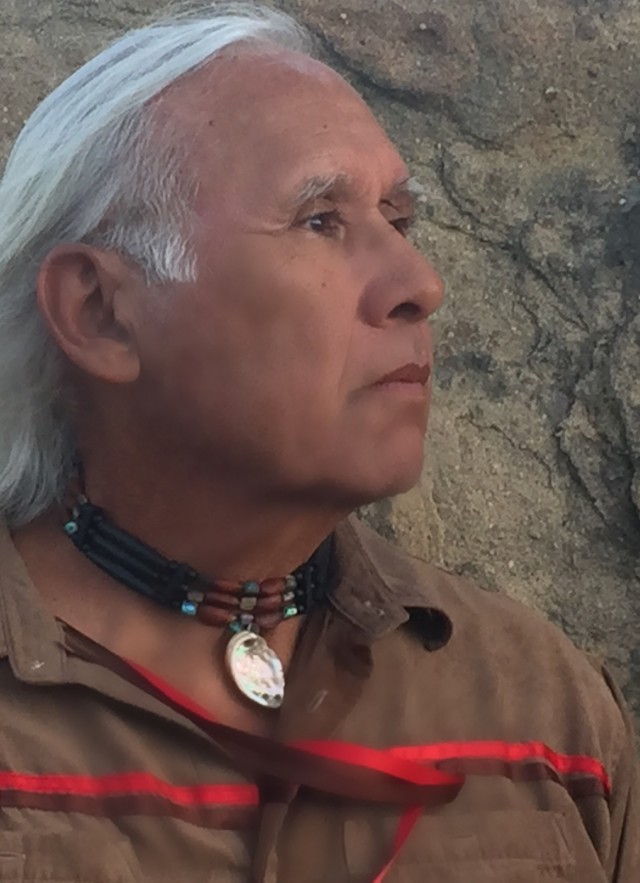

Voices of L.A. Nature: An Interview with Alan Salazar

Welcome to our story series, "Voices of L.A. Nature," where we'll hear stories from a diverse range of Angelenos about their relationships with nature in L.A.

Published November 12, 2019

This month, we're celebrating Native American heritage month, with interviews from indigenous people who call L.A. home.

Alan Salazar is a Chumash and Tataviam elder. He is also a retired juvenile probation officer, and Native storyteller. Keep reading to find out more about his relationship to nature in L.A., and hear stories about his adventures on land and sea.

On a scale of 1-10 (10 being the highest) how would your rate your love of nature today?

Without sounding overly dramatic, or pandering I'd say 10, it is a large part of my life.

Can you tell us a little bit about your career?

I worked for 20 years in probation with juvenile offenders. During that time I also began working as a Native consultant monitoring ground disturbances, and helping to protect and preserve artifacts from my ancestors . After I retired from the probation system, I started doing lectures and talks about my family and Native history over the past 200 years. The first talk I ever gave was at Fairfax elementary school in Bakersfield. At the time I was studying archaeology at Cal State Bakersfield and my professor, Dr. Sutton, was asked to speak at the elementary school for Native American month. He asked if I wanted to do it instead, since I'm Native. Turns out, it was the same school that my nephews went to!

Can you tell us a bit more about the consulting you do?

Sure. I have been monitoring groundworks over the last 25 years, particularly in Northern L.A. County in the Santa Clarita area off the 125 and 5 freeway. My Tataviam ancestral lands are here. Most people don't know that an ancient Tataviam village is under Magic Mountain. The village was called Chaguayanga, and is now covered by a staff parking lot.

I also work with developers which can be controversial. My goal is always to protect the traditional lands. But, being practical I understand that we can't always stop all development. There are lots of activists that like to get in front of the TV camera and talk about how wrong it is to develop all this land and that we need to leave it as open space. But, as soon as the project has been approved and has started you never hear from them again. It is unfortunate because there are still hundreds and thousands of opportunities to change the development for the better. It means we have to work with the developers. I'm currently consulting with FivePoint on a new development just west of Magic Mountain. The developers were going to cut down 100 mature oak trees and my tribe asked for them to be saved instead. The developers agreed to box the trees up and move them to the parks and green belts that will be part of the project. It costs about $40,000 to do this for each mature tree.

How do you incorporate nature into your daily life?

I am 68 years old and I still paddle in traditional Chumash canoes, tomols. It is very physically demanding. Every day I have to do something to keep in shape. I usually walk or bike along the coastal bike path in Ventura. As I'm going along, I see the ocean and think about the conditions. How would the tomol handle out there right now?

I grew up a country boy, and I am Native, so even when I'm out on dates with my girlfriend or driving I pay attention to nature. On dates we point out the plants we see, "There's mugwort. This one is elderberry." When I'm in my car, I'm always checking nature looking for deer and hawks and things.

Can you tell us more about your experience being a Chumash paddler?

I started paddling in 1997, and I was on the first crew that tried to make the crossing over to Anacapa and Santa Cruz Islands from the mainland. The first year we tried to cross over, it was 2001. I was the number one paddler, in the front of the tomol, and we were all buzzing. We paddled out. As we got out to 2, 3, or 4 miles, we realized that paddling in the dark was something we hadn't practiced. It was a pitch black night, with no moon and no stars. We thought we had prepared ourselves being out on the ocean in the day, building up our stamina, switching out paddlers etc. But that night taught us a lot. I am one of the few dark water paddlers, that attempted that first crossing. There are 150 paddlers total, but only 30-40 dark water paddlers. I'm going year by year, and hope to paddle next year as long as my knees and shoulders are holding up. I am going to keep paddling with my tribe as long as I physically can.

Can you share some memories of where and how you played as a kid?

I was born in San Fernando and lived there until I was about two years old. Then my dad moved us to Hanford, California, which is 30 miles south of Fresno. He wanted us to grow up in the country and land was cheaper up there. We got two acres. I remember riding horses and swimming in canals and irrigation ditches. We learned how to hunt, and at about 7 or 8 i could safely shoot a 22 rifle. We would hunt jack rabbits and cottontails, and I learned how to skin and gut them. We were taught not to shoot squirrels, or blackbirds or sparrows because we only hunted what we were going to eat.

This was the 50s and 60s so no one had AC back then. We'd go to the Kings River and play there, because it was nice and cool. There were rope swings and we would take a picnic.

What nature places did you explore as a kid in L.A.?

When I would come to visit my dad's side of the family, we'd stay in San Fernando with my grandmother and aunts and uncles and cousins. It was the late 50s and early 60s, so it was just the beginning of the San Fernando valley becoming suburban. There were orange and olive groves all around, it was the country still. I remember my dad taking me down to an abandoned slaughter house by the railroad tracks. They used to slaughter cattle there in the early 1900s. When I was around 6, 7 , or 8 my mom or dad would give me a couple of dollars and send me down to the store. I had to walk down the country roads, by the orange groves to get to the store. It was called Correos and you could get fresh tortillas there. The would be warm and right of the griddle and they would pass them to you wrapped in paper.

Do you have a funny story about a nature experience you had in L.A.?

I've worked at the Santa Susana Field Laboratory for many years. The site is 2,800 acres, and I've probably hiked over 2,500 acres of that site. When you're out and about on the site there aren't any porta potties, so just like when I was a kid and used to pee under our old cottonwood tree at night, I'd pee out there. I actually get a big kick out of it. I'm marking my territory! Letting the coyotes and other animals know I am here. The Santa Susana area is also where my Tataviam ancestors lived going back a 1000 years. So every time I pee, I'm sort of saying, "It's Alan Salazar. Your Chumash and Tataviam ancestor is HERE!"

How do you think we can make access to nature in LA more accessible for everyone? What are some of the biggest barriers?

I am a big proponent of parks. As an urban Indian, I just think it is why I do work with developers like Five Points and city park departments. I've worked with the Ventura and L.A. park and rec departments for most of my adult life. The more parks we have to play in, with nature, and swings, and grass, the better. I've worked with a lot of poor kids and their families, they are just trying to survive. If a park is not close by to where they live, they aren't going to go. There are farm labor kids I've worked with in Oxnard who live 2-3 miles from the beach, and they've never been. Their parents work 9, 10, 11 hour days, they don't have time to drive to a park far away. We need more parks and trail heads in neighborhoods. Access to nature that families can just walk to.

Land acknowledgements are becoming more and more mainstream, what do you think about them?

Most tribes want to be acknowledged that you are on their tribal land. The Ventureño Chumash and the Fernandeño Tataviam do not have federal recognition, so it is extremely important to us. The Fernandeño Tataviam are traditionally from northern L.A. County. Most Los Angeles residents have never heard of us, let alone know that they are living on tribal land. We are currently under review by the Bureau of Indian Affairs for our federal recognition. If we are approved we will be the first tribe in L.A. County to be a federally recognized tribe, that will be huge.

Follow Alan: www.mynativestories.com