Hot Rocks and Natural Beauties

During Curator Emeritus of Mineral Sciences Dr. Anthony Kampf's tenure at NHM, his work with minerals has sometimes seemed like a true crime drama.

Originally Pubilshed in April 2019

Dr. Anthony Kampf, NHM’s Curator Emeritus of Mineral Sciences, says his work over the years has sometimes seemed like an episode of the TV show CSI. He has been called upon by the Los Angeles police and criminal courts to conduct “forensic mineralogy”—unravelling mysteries, detecting fakes, and spotting signs of human intervention by following clues to where the mineral specimens were buried.

“Gluing crystals on rocks, hiding fractures, polishing faces, adding color—these are just a few of the things people do to minerals to make them appear more valuable,” he says. “It’s part of the job of a mineral curator to recognize that, just as it’s an art expert’s job to spot forged paintings.”

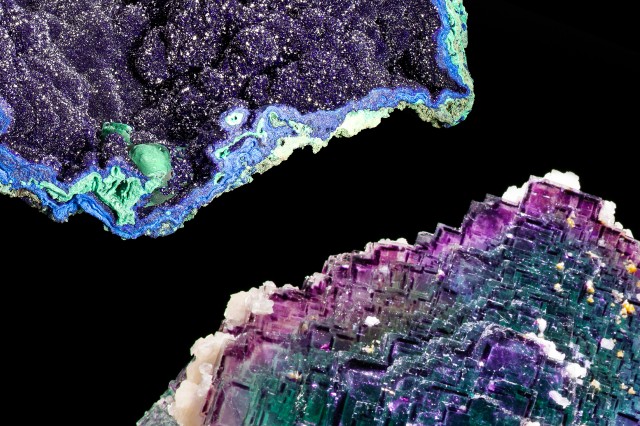

Sitting in a locked laboratory off of the museum’s Gem and Mineral Hall, Kampf said there’s a fine line between a minor enhancement and major overhaul. Cleaning, repairing, and stabilizing are often necessary to reveal, restore, or preserve a specimen’s natural appearance. Crystals often must be put back together and “articulated” as they would be in nature to ready for them for display. Kampf likens this to dinosaur fossils that are arranged and mounted in the correct position, such as those in the Dinosaur Hall. Fakery begins, though, when people drastically alter (improve) a specimen’s natural appearance—in the most extreme cases completely creating specimens by taking portions of one and attaching them to another. The mineral’s “provenance” can also be fudged. A gold nugget purportedly from Australia could pass for one from California. (Look for real Golden State gold in cases in the Gem and Mineral Hall.)

REAL GEMS

With gems, which are all cut and polished, enhancement on the outside is a given. But a gem investigator needs a microscope or even more high-tech equipment to expose any fakery inside. Emeralds, for instance, are commonly oiled, topaz is irradiated, and turquoise is impregnated with plastic.

Mineralogical sleuthing aside, Kampf has spent much of his time as a mineralogist solving natural mysteries by describing new minerals. He has named more than 150—a good chunk of the roughly 6,000 minerals known to science. To make an ID, he uses a high-tech x-ray diffraction system to record a digital pattern, which he compares to a huge database of crystalline materials. Then he uses the same system to solve the atomic puzzle that is the “crystal structure.”

“It is the museum’s responsibility to exhibit minerals in their natural appearance,” he says. “Just as in art, you have to preserve the artist’s intent.”

TOUCHABLE MINERALS

Get the feel of minerals, meteorites, and even polished gemstones, such as nephrite jade, in the Gem and Mineral Hall every day.