Coyotes of L.A.’s Urban Core: Using Science to Separate Fact from Fiction

The Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area formally announced this week that they launched the first study on urban coyotes of Los Angeles.

The Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area formally announced this week that they launched the first study on urban coyotes of Los Angeles. I was fortunate enough to be able to help with the processing of C-145, a coyote that was captured in Silver Lake.

It was half past midnight and I was getting ready to turn off Jimmy Kimmel Live and head to bed, when all of the sudden I received a text from Justin Brown, National Park Service Ecologist, stating “trap triggered silver lake.” I quickly put my boots on, said bye to my wife, and rushed out the door. My 6 minute commute from my Los Feliz apartment to the Silver Lake location was a very surreal experience as I drove by the dog park where I would bring my childhood dog and the recreation center where my brothers and I played little league baseball and football. It felt as if my childhood and career were intersecting at that one moment. Instead of driving by these landmarks to watch my little brothers play little league, the usually busy streets were now empty and I was on my way to help collar a coyote. My excitement was a bit tempered because I had gone through the same exact exercise 22 days earlier, but when I arrived at the location that night the coyote had escaped from the trap as Justin approached. This time, however, Justin had safely secured the animal. I slowly drove onto a dirt road and found Justin’s NPS truck. I parked next to Justin’s truck, which smelled like carnivore lure (i.e., skunk essence) and headed towards the capture site with my dimly lit headlamp, passing a carcass of a hooved animal along the way that had been used as bait. I arrived at the trap site and found Justin hovering over the safely and humanely restrained coyote. We processed the animal by taking blood, tissue samples, body measurements, and placing a GPS collar around its neck. Meanwhile, we could hear coyotes calling nearby. The male coyote was released and quickly vanished into the darkness. We cleaned up and put away all of the capture kit materials before heading back to our vehicles. Before Justin and I parted ways that night, he showed me some locations visited by a different coyote that was captured and GPS-collared a few nights earlier (C-144) in an even more urban setting within the Westlake neighborhood (near downtown Los Angeles). I was amazed to see that this coyote had crossed the 101 freeway multiple times and was using the same neighborhood where I attended grammar school and high school, and now pass by every day during my work commute. As the shock and adrenaline wore off during my short drive home, it was replaced by excitement not just from the perspective of an urban carnivore researcher, but as an Angeleno who has a long history with coyotes. I grew up in the Los Feliz neighborhood, which is prime coyote habitat due to its proximity to a large urban wilderness called Griffith Park. My experiences with coyotes ranged from having my first pet, a black cat named “Whiskey,” getting killed by coyotes to being a professional scientist studying their ability to cross freeways and other conservation challenges.

Urban coyotes have become an increasingly dividing topic here in Los Angeles and throughout the Southern California region. Rumors of coyotes becoming bolder, more aggressive, and increasingly common in residential areas have spread largely thanks to the media and persuasive community members. Some have suggested the drought is impacting the frequency of human-coyote conflict, although there is no data to support these claims. Others suspect the conflict is a result of continued habituation of urban coyotes due to intentional and unintentional coyote feeding via outdoor pet food and fallen fruit left on the ground. The truth about coyote behavior and urban ecology in Los Angeles is mostly still a mystery due to a lack of research on urban coyotes. However, recent research on local suburban coyotes suggested that even the most urban of those studied had by in large retained similar behavior to their more rural counterparts even during periods of drought. Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area biologists studied 110 local coyotes between 1996 and 2004 in the suburbs of L.A. and Ventura Counties.* Their research provided some fascinating insights. For example, 77% of the home ranges of suburban coyotes were within natural areas.* Although coyote diets in more urban areas consisted of more anthropogenic items, coyote diets within the most fragmented areas still consisted mostly of natural prey and fruit. Only 1% of coyote diets within very fragmented areas consisted of domestic cats, including feral cats. Finally, out of 110 L.A. urban coyotes captured, collared, and studied, none were “nuisance coyotes”, which suggests that even the most urban coyotes are not reliant on handouts (e.g., pet food) or pets. Results of long-term research on urban coyotes in Chicago showed similar trends.* Most recently, Roland Kays and fellow researchers from North Carolina State University and the Smithsonian Institution organized a large-scale citizen science camera trap study called eMammal. This ongoing study, across 6 eastern states, was monitoring both developed and protected natural areas with motion detecting camera traps. Kays and colleagues found that domestic cats were more nocturnal or entirely absent from more natural habitat with coyotes present, and were more diurnal and active in developed areas such as backyards, which were almost entirely devoid of coyote activity.

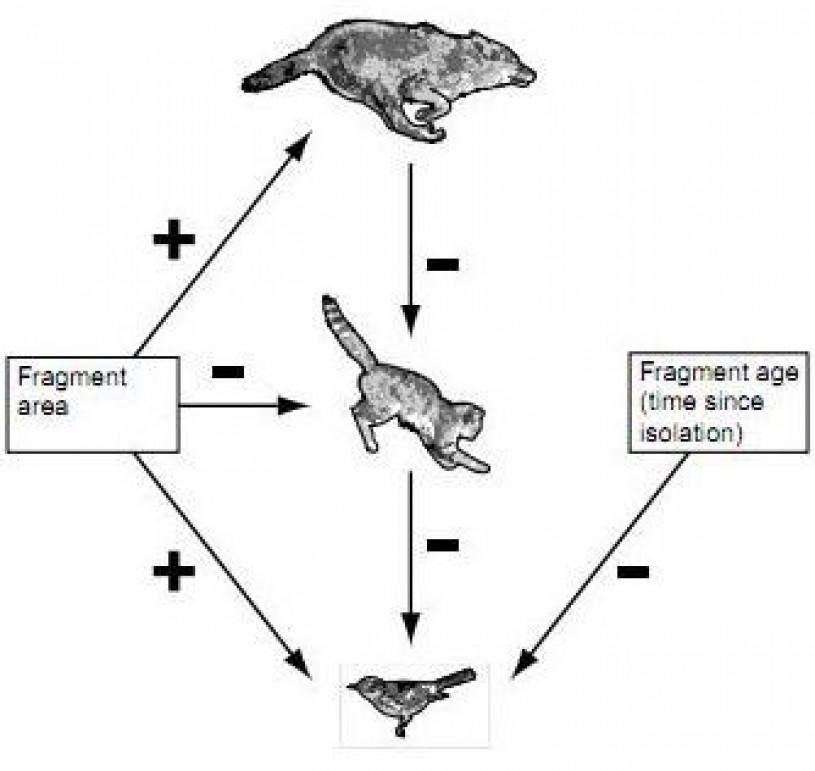

The published results support data from a previous study in San Diego that suggested that the patches of habitat without coyotes had increased feral cat and small predator activity, which in turn resulted in increased predation of songbird species.

Diagram depicts influence of coyote presence on feral cat and bird populations, Photo credit: Crooks and Soulé 1999. How do these results apply to coyotes that seem to be living deep within L.A.’s urban core? Preliminary data from camera trap studies conducted by the NHMLA/USC Spatial Sciences Institute Baldwin Hills Biota Study and the Griffith Park Connectivity Study mirrors the trends of domestic cat and coyote interactions from the east coast, San Diego, and Chicago. For instance, we are noticing that domestic cats are nearly absent from the coyote-rich park interiors of Griffith Park whereas cats are being documented throughout the Baldwin Hills to the southwest. The Baldwin Hills are smaller and more fragmented, which may explain why coyotes seem to generally be more scarce there than in less fragmented habitat like Griffith Park. As more urban coyote results emerge from various research projects, it is increasingly apparent that coyotes are important indicators of ecosystem health and connectivity in even the most urban settings.

Spatial Sciences Institute Baldwin Hills Biota Study Similar to squirrels, mule deer, and other iconic L.A. mammals, coyotes have largely been taken for granted and historically overlooked by researchers, especially in urban areas. They are the animal everybody thinks they are familiar with but actually know very little about. Hopefully C-144 and C-145 become myth-busting urban coyote ambassadors that inspire Angelenos to coexist with this species. It remains to be seen whether these two coyotes display similar patterns to the suburban coyotes studied a decade ago. However, preliminary results of their use of the urban landscape are already surprising biologists because instead of spending most of their time in natural areas, they are spending most of their time in developed areas. Although coyotes have been around since the Ice Age, it is clear that they have certain habitat and space limitations. Also, once coyote populations are removed from neighborhoods that become too fragmented, people need to consider how that will change L.A.’s landscape. Are we OK with an L.A. with less biodiversity, where domestic cats are the dominant predator, risking the fate of urban bird and reptile populations? If not, what can we do to make sure coyotes and other predators have the space and resources they need to continue filling their important roles as top predators in our L.A. ecosystems? It is clear that responsible coyote management must begin with the collection of baseline information about their ecology within our most urban communities. *Stanley D. Gehrt and Seth P. D. Riley, "Coyotes (Canis latrans)" in Urban Carnivores: Ecology, Conflict, and Conservation, Stanley D. Gehrt, Seth P. D. Riley, and Brian L. Cypher eds., JHU Press, 2010, ISBN 0801893895, pp. 79–96.