Out of every single dog on the planet, yours is the best, isn't it?

I believe you because I feel the exact same way. In fact, I think most people have agreed with that sentiment for thousands of years. Dogs are one of the first animals ever to be domesticated by humans, and they've been beloved worldwide ever since, especially here in the Americas. Though there are no bumper stickers showing proud breed owners or Instagram photos of ancient American dogs, we have the next best thing; archaeological evidence. If you enter the Visible Vault of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, you may notice a little clay dog that someone handcrafted about 2,000 years ago. This bright red ceramic figurine stands at about 9.5 inches tall and has a stout, pudgy appearance that makes you want to give it a hug. The figurine that can be seen in the Visible Vault is called a Colima Dog, and it is not the only one. Similar ceramic figurines depicting dogs can be found in ancient shaft tombs all throughout Mesoamerica, most notably in the western Mexican state of Colima. They usually have short, squat, round bodies with perky ears and are covered in red slip, a mixture of water and fine clay used to intensify the natural red coloration of ceramics.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Rosanna Esparza Ahrens, left, holds a doll created by her grandmother, Guadalupe Salazar. Ofelia Esparza, right, holds a doll brought to her by her mother from Mexico. Ofelia estimates the doll to be about a century old.

Steven Mendoza

My own Chihuahua by the name of Babygirl shares similar features to the Colima Dog figurines we have in our collection, including a small, squat body and perky ears.

1 of 1

Rosanna Esparza Ahrens, left, holds a doll created by her grandmother, Guadalupe Salazar. Ofelia Esparza, right, holds a doll brought to her by her mother from Mexico. Ofelia estimates the doll to be about a century old.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

My own Chihuahua by the name of Babygirl shares similar features to the Colima Dog figurines we have in our collection, including a small, squat body and perky ears.

Steven Mendoza

While some ancient cultures are studied by interpreting ancient texts or art, archaeological interpretations of ceramic figurines found in shaft tombs are crucial to our understanding of the early Americas. These dog figurines help us understand the story of a complex relationship between humans and animals in the early Americas. While the dog on display in the Visible Vault is depicted sitting (like a good puppy), these dogs have different iterations. Some are depicted as having wrinkles, indicating these dogs likely did not have any fur. Others have been depicted dancing with each other, smiling, eating human food, laughing, wearing masks, and doing other human activities. Living in westernized culture, we often perceive our relationship with animals as a distinct divide; a hierarchy with people at the top and other animals at the bottom. This idea of hierarchy is rooted in western culture and does not examine animals in dynamic terms. The dogs of Mesoamerica had a complex relationship with humans and were often seen as equals that served important roles and functions in everyday life. The Colima Dogs help us understand that story.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Anthropology Department

This figurine, circa 800-1250 CE, is from Colima, Mexico. What are some of the similarities and differences you notice between this dog and all the others?

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Anthropology Department

This is a side view of the previous figurine—circa 800-1250 CE and from Colima, Mexico. What are some of the similarities and differences you notice between this dog and all the others?

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Anthropology Department

This figurine, circa 959 CE, is from Colima, Mexico. What are some of the similarities and differences you notice between this dog and all the others?

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Anthropology Department

This figurine, circa 800-1250 CE, is from Colima, Mexico. What are some of the similarities and differences you notice between this dog and all the others?

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Anthropology Department

This figurine, circa 300-1250 CE, is from Colima, Mexico. What are some of the similarities and differences you notice between this dog and all the others?

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Anthropology Department

This is a view from the front of the previous figurine—circa 959 CE from Colima, Mexico. What are some of the similarities and differences you notice between this dog and all the others?

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Anthropology Department

The origins and age of this figurine are mostly unknown— it could have originated from Mexico, Peru, or what is now the Southwestern United States.

1 of 1

This figurine, circa 800-1250 CE, is from Colima, Mexico. What are some of the similarities and differences you notice between this dog and all the others?

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Anthropology Department

This is a side view of the previous figurine—circa 800-1250 CE and from Colima, Mexico. What are some of the similarities and differences you notice between this dog and all the others?

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Anthropology Department

This figurine, circa 959 CE, is from Colima, Mexico. What are some of the similarities and differences you notice between this dog and all the others?

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Anthropology Department

This figurine, circa 800-1250 CE, is from Colima, Mexico. What are some of the similarities and differences you notice between this dog and all the others?

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Anthropology Department

This figurine, circa 300-1250 CE, is from Colima, Mexico. What are some of the similarities and differences you notice between this dog and all the others?

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Anthropology Department

This is a view from the front of the previous figurine—circa 959 CE from Colima, Mexico. What are some of the similarities and differences you notice between this dog and all the others?

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Anthropology Department

The origins and age of this figurine are mostly unknown— it could have originated from Mexico, Peru, or what is now the Southwestern United States.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Anthropology Department

Puppy Chow

As you scroll through the above images of Colima Dogs in the Museums collection, what are some of the features that stand out to you? You may notice that the dogs are all a little chubby. In the ancient Americas, pack animals like cows, pigs, and sheep did not exist in the region. Therefore, the people of ancient Mexico consumed a heavily plant-based diet, consisting mainly of corn, squash, and beans. To bring protein into their diet, dogs were domesticated and bred as a nutritious source of food-- along with turkey and wattle duck. Certain canines were bred specifically to be small and were fattened up with leftover food scraps, yielding the maximum amount of protein for a minimal caloric investment. While some canines were bred to be eaten, precolonial dogs also served a variety of other purposes. Some dogs were kept as pets and would never be consumed; others were bred for ritualistic sacrifice. They were also used as watchdogs and to transport goods. Some were even used as therapy dogs, specifically bred to run hot so they could be used as a warm compress that you could hold against any bodily aches and pains. Imagine your doctor prescribed you a warm pup to alleviate muscle soreness, with the added bonus of a furry companion!

Dogs were seen as a source of life, providing food, healing, and companionship, but their undying loyalty also linked them to the afterlife. Colima Dog figurines were often left in shaft tombs as a funerary offering of food and protection for the dead's underworld journey. Throughout Mesoamerica, many cultural groups believed that if you were kind to your dog in life, it would aid you well in the afterlife, allowing you to grab onto their tail as they tow you across a body of water to the land of the dead. Other groups believed that the gates to the afterlife were guarded by a dog that was easily pacified by tortillas. Even the Aztec god of death Xolotl had a dog head, and it was said that the dogs on earth were sent to be his emissaries. Much like today, dogs held a prized position in Mesoamerican culture-- but all that changed with the arrival of the Spanish.

Lucas, Flickr

This dog-headed sculpture from the Museum Nacional de Antropología de México is of Xolotl, the Aztec God of Death. Dogs were thought to be emissaries of Xolotl.

Lucas, Flickr

Mexican hairless dogs, Xoloitzcuintli, received their name from the Aztec god of death Xolotl. Xolo derives from Xolotl, the name of the deity and itzcuitli is the Aztec word for dog.

1 of 1

This dog-headed sculpture from the Museum Nacional de Antropología de México is of Xolotl, the Aztec God of Death. Dogs were thought to be emissaries of Xolotl.

Lucas, Flickr

Mexican hairless dogs, Xoloitzcuintli, received their name from the Aztec god of death Xolotl. Xolo derives from Xolotl, the name of the deity and itzcuitli is the Aztec word for dog.

Lucas, Flickr

Dog Eat Dog World

In 1519, the Spanish pushed their way into the Americas, bringing their own culture, language, food, diseases, and of course, dogs. The role of dogs that the Spanish brought differed entirely from the roles dogs served in the Americas. The Spanish brought war dogs with them, bred to help them conquer, and used by missionaries to inflict corporal punishment on native groups. The arrival of these new European breeds changed the perception of dogs completely. Distinctions were made between European dogs with fur and Indigenous dogs that lacked fur. To these ancient communities, the European dogs with fur became associated with violence, plague, and even bad weather. In contrast, the hairless dogs bred in the Americans were still celebrated as sacred symbols. Hairless dog meat was more highly esteemed than the strange new meats of cow and sheep the Spanish had brought. Some Spanish codices describe that even the Spanish consumed dog meat at extremely high rates. The spiritual and culinary value that ancient Mesoamerican people placed on their dogs was labeled as a pagan custom that was in direct opposition to the spread of Catholicism, and Indigenous dogs were systematically eradicated. The hairless dogs of the Americas were brought to the brink of extinction, with only a few remaining groups surviving by finding safety and refuge in the mountainous regions of Mexico.

Xoloitzcuintli, Xoloizcuintle, Facebook

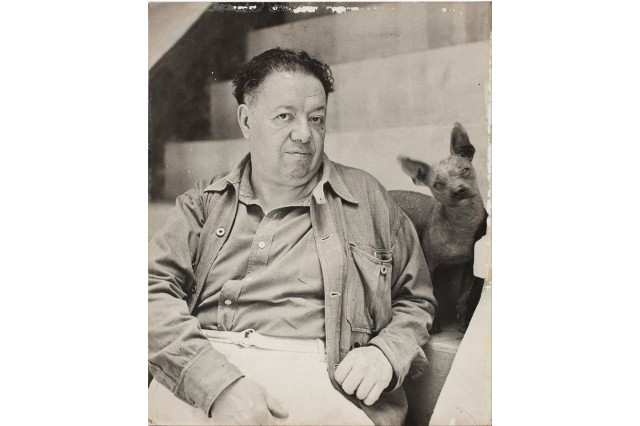

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera owned a group of Xoloitzcuintlis that they featured in their paintings and photography-- in an effort to reclaim often stigmatized Indigenous symbols. Their dogs’ descendants can still be seen living at El Museo Dolores Olmedo today in Mexico City.

Xoloitzcuintli, Xoloizcuintle, Facebook

Diego Rivera was a prominent Mexican painter and was married twice to Frida Kahlo. Diego, known for his frescoes, famously painted a Xolo baring its teeth at the invading Spaniards as they arrived in Vera Cruz, Mexico.

Libby Rosof, Flickr

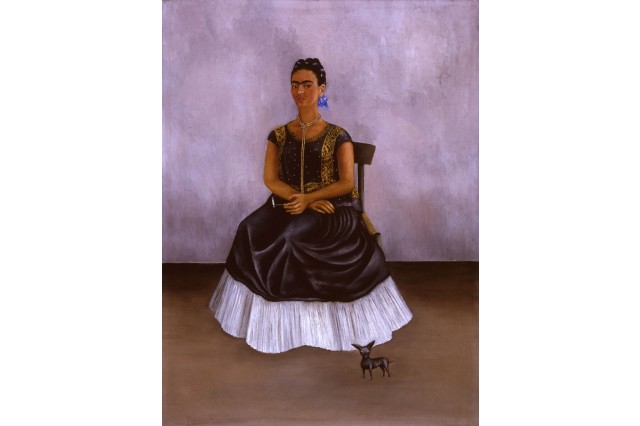

This Frida Kahlo painting, titled Itzcuintli the Dog and Me, is from 1938. It is a self-portrait of Frida with one of her Xoloitzcuintli dogs. She was known to have many dogs and keep other pets like birds, monkeys, and even deer.

1 of 1

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera owned a group of Xoloitzcuintlis that they featured in their paintings and photography-- in an effort to reclaim often stigmatized Indigenous symbols. Their dogs’ descendants can still be seen living at El Museo Dolores Olmedo today in Mexico City.

Xoloitzcuintli, Xoloizcuintle, Facebook

Diego Rivera was a prominent Mexican painter and was married twice to Frida Kahlo. Diego, known for his frescoes, famously painted a Xolo baring its teeth at the invading Spaniards as they arrived in Vera Cruz, Mexico.

Xoloitzcuintli, Xoloizcuintle, Facebook

This Frida Kahlo painting, titled Itzcuintli the Dog and Me, is from 1938. It is a self-portrait of Frida with one of her Xoloitzcuintli dogs. She was known to have many dogs and keep other pets like birds, monkeys, and even deer.

Libby Rosof, Flickr

Underdogs

By the time Mexico launched its war for independence in the early 1810s, the population of Native dogs was on the brink of extinction. Over time the few remaining dogs that were once wild in the mountains were re-domesticated and saved by Indigenous groups that lived in those regions; however, their numbers remained extremely low as they only remained in isolated groups. The Xoloitzcuintli and Chihuahuas we know today may be descendants of these isolated redomesticated groups, but their true lineage is hard to trace as these dogs were thought to be extinct by westernized dog institutions like the American Kennel Club. After the Mexican Revolution of 1910, artists and activists like Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera helped reintroduce these dogs to Mexican pop culture with their efforts to reclaim often stigmatized Indigenous symbols in their paintings and photography. Artists of today embrace the past by making recreations of these Colima Dog figurines and incorporating them in their artwork, many in the likeness of ancient artifacts.

Zeferino Llamas

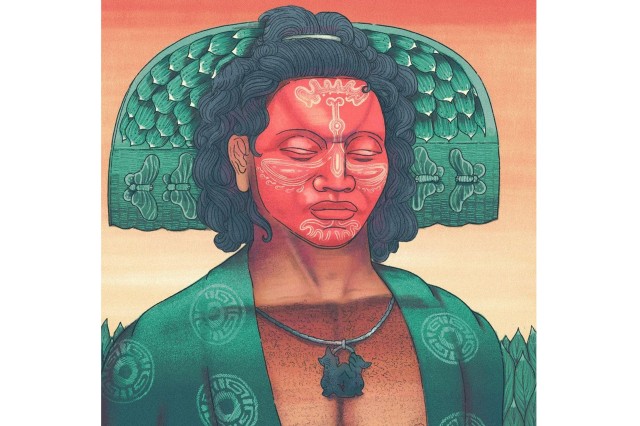

Artist Zeferino Llamas draws inspiration from nature and indigenous Mexican symbols, including Colima Dogs.

@xolitomiomx, Instagram

Celebrating precolonial Mexican art and art form is a passion for organizations like Xolito Mío y Coatlicue Arte, located in Mexico City. Here the Colima Dogs have been recreated using mud/clay in creative ways, like these planters.

The pre-Hispanic dogs are depicted by many artists in Mexico, and this figurine is a replica of an artifact that is currently in the Princeton University Art Museum Collection.

@xolitomiomx, Instagram

@seherone, Instagram

This mural, created by artist David Piñón, features a Colima Dog and is a postcard to the community of Atlacomulco De Fabela, Mexico. The word "AMBARO" is the Mazahuan word for Atlacomulco, which are the Indigenous people of the area.

Zeferino Llamas, Instagram

Artist Zeferino Llamas embraces the past by including the Colima Dancing Dogs on the necklace of his work titled Xochipilli.

1 of 1

Artist Zeferino Llamas draws inspiration from nature and indigenous Mexican symbols, including Colima Dogs.

Zeferino Llamas

Celebrating precolonial Mexican art and art form is a passion for organizations like Xolito Mío y Coatlicue Arte, located in Mexico City. Here the Colima Dogs have been recreated using mud/clay in creative ways, like these planters.

@xolitomiomx, Instagram

The pre-Hispanic dogs are depicted by many artists in Mexico, and this figurine is a replica of an artifact that is currently in the Princeton University Art Museum Collection.

@xolitomiomx, Instagram

This mural, created by artist David Piñón, features a Colima Dog and is a postcard to the community of Atlacomulco De Fabela, Mexico. The word "AMBARO" is the Mazahuan word for Atlacomulco, which are the Indigenous people of the area.

@seherone, Instagram

Artist Zeferino Llamas embraces the past by including the Colima Dancing Dogs on the necklace of his work titled Xochipilli.

Zeferino Llamas, Instagram

Collections Practices… Ruff, But Getting Better

If you have ever watched Antiques Roadshow, or any show where people bring their treasures for expert analysis, you may have wondered, “how did that piece come to live in that attic?” Answering that question can be easy for some items and more difficult for others since objects have been collected and moved for thousands of years by people. When an item is removed from its place of origin, it is important to document its earliest known history so that the story and context of the item are preserved-- in museums this is called provenance, which is derived from the French word provenir, meaning “to come from.”

Unfortunately, the provenance of many items in public and private collections is incomplete. For centuries, artifacts all throughout the Americas have been looted from their place of origin and sold for profit to vendors, private collectors, and yes, even to museums. Some of the Colima Dogs in the Museum collection have gaps of historical context and remain shrouded in mystery since they were purchased decades ago from private collectors. Anthropology Collections Manager Chris Coleman explained that NHM no longer acquires these types of collections due to international cultural property laws and changing attitudes towards collecting other countries' cultural heritage. In addition, the Museum has recently partnered with the Getty Research Institute's Stendahl Art Galleries Archives to research the records and actively work towards determining more complete provenience and collection information. The Stendahl Art Galleries were major contributors to our Ancient Latin American collections. Coleman further explained that these artifacts still have intrinsic value and are an important part of our museum collection from an art historical context and can be used as stylistic guides to interpret other Mesoamerican artifacts. The museum remains hopeful that with each passing year new innovative technologies arise that push our research capabilities to new levels. For example, researchers are now able to examine atomic isotopes within soil samples that can help identify soil components and even locality in some cases. Maybe one day we will be able to trace these figurines back to the places they were made.

Our Best Friends

Often when we look at items on display in the museum, separated from us by a sheet of glass and thousands of years, it is easy to feel disconnected from the people who made them. Here is something to consider-- the cultural artifacts in Museums were made by people, for people who are just like us. When I look at the ceramic Colima Dog on display, I am reminded of objects in our everyday lives that pay homage to the dogs we love, like my mom’s ceramic mug sculpted to look like the head of a rottweiler. If you are a dog owner yourself, maybe you have something similar, a framed photograph of your dog or a T-shirt with their face on it. Consider why you purchased that item? How does it make you feel? Maybe those feelings of warmth, connection, protection, and companionship are some of the emotions that the people who sculpted these Colima Dogs were trying to capture as well.

A Note from the Author - Steven Mendoza, Museum Educator

When you work in a museum, you come to realize that everything has a story. Some of these stories are very well documented, while others take a little more digging to uncover. When I first saw this dog sitting in the Visible Vault, I knew that this was a story I had to get to the bottom of. Now more than ever, it is important to learn the truth behind our own cultural histories, as well as the histories of our neighbors. We all have more in common than you may expect! By researching these dogs, I felt a connection between myself and my ancestry; we all appreciate a good Chihuahua! The next time you see an object that interests you, I encourage you to dig a little deeper, you never know what you might find!