Beyond Gender: Indigenous Perspectives, Muxe

A limited series on some of the world's third gender Indigenous people

Published September 15, 2020

Source for the above photo: Facebook - Vela Muxe Los Angeles

Connecting Our Past and Present

The Anthropology Department in partnership with the Community Engagement team are excited to share contemporary stories and NHM collections items spotlighting the Mapuche, Muxe, Fa'afafine and Fa'afatama. Follow along for two additional stories linked below highlighting these vibrant and diverse third gender communities from all around the world.

The gender binary system that exists within many western societies is far from a universal concept.

In fact, numerous Indigenous communities around the world do not conflate gender and sex; rather, they recognize a third or more genders within their societies. Individuals that identify as a third gender many times have visible and socially recognizable positions within their societies and sometimes are thought to have unique or supernatural power that they can access because of their gender identity. However, as European influence and westernized ideologies began to spread and were, in many cases, forced upon Indigenous societies, third genders diminished, along with so many other Indigenous cultural traditions. Nevertheless, the cultural belief and acceptance of genders beyond a binary system still exist in traditional societies around the world. In many cases, these third gender individuals represent continuing cultural traditions and maintain aspects of cultural identity within their communities.

Within a Western and Christian ideological framework, individuals who identify as a third gender are often thought of as part of the LGBTQ community. This classification actually distorts the concept of a third gender and reflects a culture that historically recognizes only two genders based on sex assigned at birth - male or female – and anyone acting outside of the cultural norms for their sex may be classified as homosexual, gender queer, or transgender, among other classifications. In societies that recognize a third gender, the gender classification is not based on sexual identity, but rather on gender identity and spirituality. Individuals who identify with a cultural third gender are, in fact, acting within their gender/sex norm.

Muxes, Mexico

The Muxes (pronounced mu-shay), a recognized third gender among the Zapotec people in Oaxaca, maintain traditional dress, the Zapotec language, and other cultural traditions that are less prevalent among the broader Zapotec community. In Juchitán de Zaragoza, a small town on the Istmo de Tehuantepec in the state of Oaxaca, there remains a large population of Muxes who have been celebrated since pre-colonization times. The wider acceptance of a third gender among the community may be traced to the belief that individuals who identify as Muxes are part of the culture and its traditions, not separate from it.

The Isthmus of Tehuantepec is famous for its Tehuana traje, or traditional dress, which has beautiful floral embroidery. Geographically, the Isthmus was exposed to items from China and Southeast Asia not seen in other parts of the Americas, and the embroidered silks from those areas influenced the women of Tehuantepec to create their own embroidered garments. Selling and trading these popular, elaborate garments garnered a strong matriarchal society of independent women who are financially independent and respected as the main source of income for the family. This relative equality of genders in the region also contributes to the widespread acceptance of Muxes.

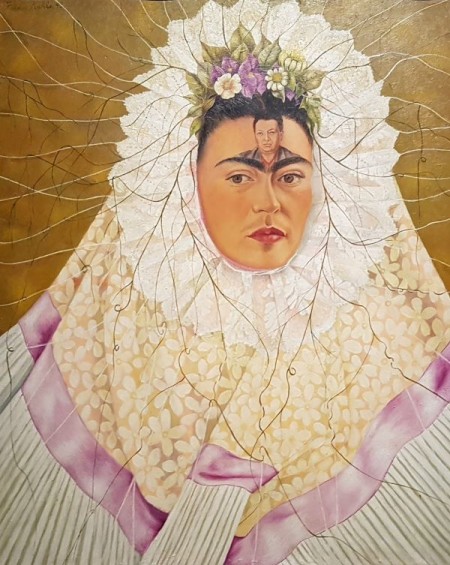

The huipil grande, also called a resplendor (meaning "radiate" in Spanish), is likely the most iconic element of traditional Tehuana traje. The huipil grande is worn with the ruffled collar framing the face. Frida Kahlo featured the huipil grande in two of her paintings, making the item famous to people outside of Mexico.

In the painting (right), Self-Portrait as a Tehuana (Diego on My Mind), 1943, she chose to show the garment as it would be worn to church or on special occasions. Frida Kahlo not only brought worldwide popularity to the Tehuana traje through

her paintings, she also adopted the traditional attire into her own identity. Frida’s mother was Oaxacan and she often wore the outfits because she admired the strength and independence of the region’s women. As a woman who challenged the gender stereotypes and boundaries of the art world, she is hailed as an icon among the Muxe community.

Celebration of the vibrant Tehuana traje and recognition of the strong Muxe community in Oaxaca continues to the present day. The beautifully embroidered traje and huipil grande are most notably on display in the Tehuantepec region during velas, or time-honored fiestas. Muxes maintain this essential aspect of Tehuantepec culture by largely organizing these fiestas and wearing traditional attire. In 2013, Vice covered a three-day vela dedicated to the Muxe community held in Juchitan every November.

Muxe still thrive today.

Every November a celebration known as the Vigil (vela) of the Authentic Intrepid Searchers of Danger takes place in the city of Juchitán, Oaxaca, in Mexico. In this documentary VICE travels to Juchitán to meet members of the Muxe of Zapotec culture, and to hang out at the Vigil, which VICE described as "one of the best parties we've ever been to".

Los Angeles hosts its own Muxe vela, Vela Muxe Los Angeles. Pictured here (right to left) is Maritza the Muxe Queen in 2014, Noelia the 2016 Muxe Queen, and Brianna the 2015 Muxe Queen.

In December 2019, Vogue México & Latinoamérica made history by featuring Muxe Estrella Vazqueza on the cover of the magazine for the first time.

In the Vogue cover on the left you can see Estrella wears the huipil grande the way that it is worn on full-dress occasions so that the wide frill surrounds the wearer like radiating beams of light while the collar and sleeves hang down behind.

Recommended Reading

Behind the Mask: Gender Hybridity in a Zapotec Community by Alfredo Mirandé

After seeing a video of a muxe vela, or festival, sociologist Alfredo Mirandé was intrigued by the contradiction between Mexico’s patriarchal reputation and its warm acceptance of los muxes. Seeking to get past traditional Mexican masculinity, he presents us with Behind the Mask, which combines historical analysis, ethnographic field research, and interviews conducted with los muxes of Juchitán over a period of seven years. Mirandé observed community events, attended muxe velas, and interviewed both muxes and other Juchitán residents. Prefaced by an overview of the study methods and sample, the book challenges the ideology of a male-dominated Mexican society driven by the cult of machismo, featuring photos alongside four appendixes.

Delving into many aspects of their lives and culture, the author discusses how the muxes are perceived by others, how the muxes perceive themselves, and the acceptance of a third gender status among various North American indigenous groups. Mirandé compares traditional Mexicano/Latino conceptions of gender and sexuality to modern or Western object choice configurations. He concludes by proposing a new hybrid model for rethinking these seemingly contradictory and conflicting gender systems.