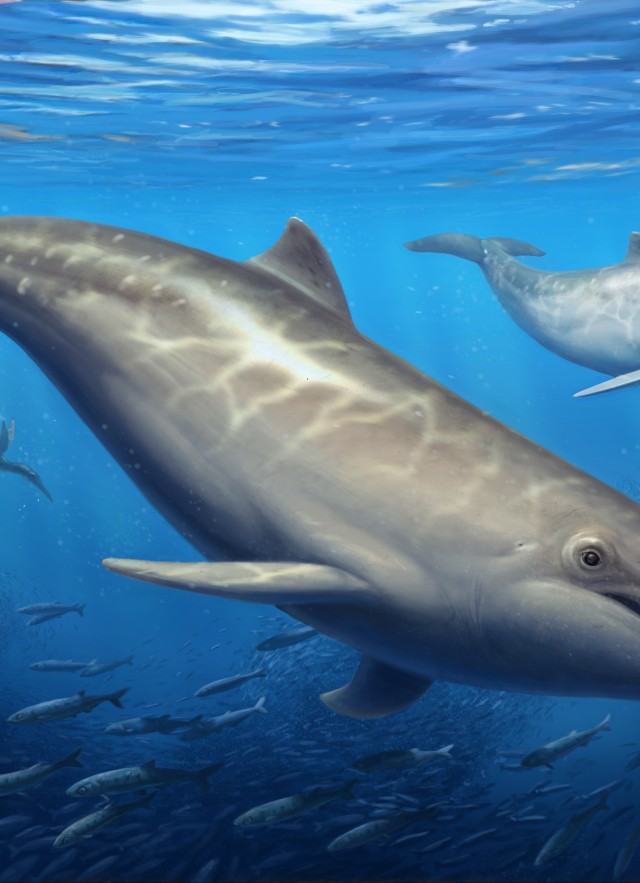

Los Angeles, CA (June 23, 2023) — Have you ever wondered what the earliest ancestors of today’s dolphins looked like? Then look no further and meet Olympicetus thalassodon, a new species of early odontocete, or toothed whale, that swam along the North Pacific coastline around 28 million years ago. This new species is one of several that are helping us understand the early history and diversification of modern dolphins, porpoises, and other toothed whales. The new species is described in a new study published in the open access journal PeerJ by Puerto Rican paleontologist Jorge Velez-Juarbe, Associate Curator of Marine Mammals at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

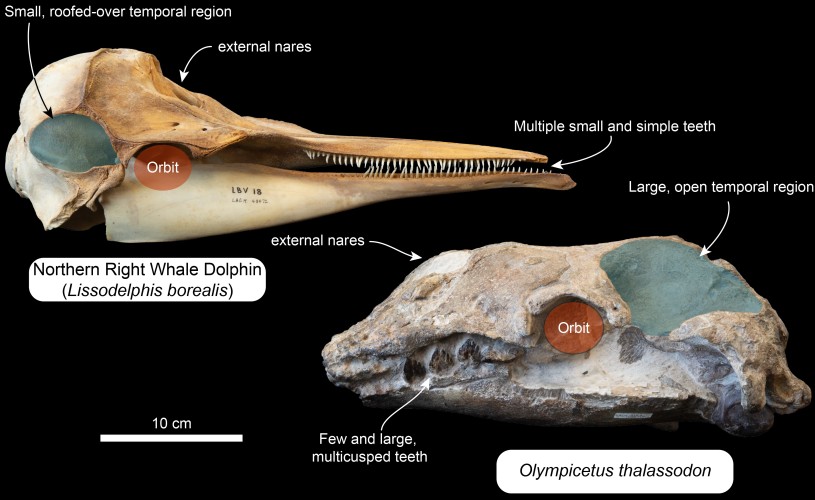

“Olympicetus thalassodon and its close relatives show a combination of features that truly sets them apart from any other group of toothed whales. Some of these characteristics, like the multi-cusped teeth, symmetric skulls, and forward position of the nostrils makes them look more like an intermediate between archaic whales and the dolphins we are more familiar with,” says Dr. Velez-Juarbe.

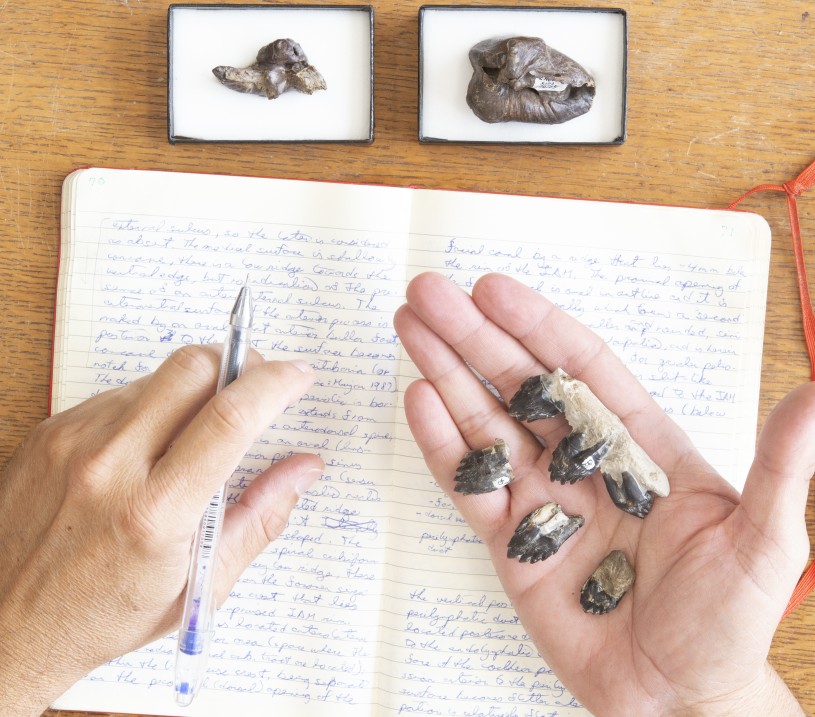

But Olympicetus thalassodon was not alone, the remains of two other closely related odontocetes were described in the same paper. The fossils were all collected from a geologic unit called the Pysht Formation, exposed along the coast of the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State and dated to between 26.5–30.5 million years.

The study further revealed that Olympicetus and its close kin belonged to a family called Simocetidae, a group so far known only from the North Pacific and one of the earliest diverging groups of toothed whales. Simocetids formed part of an unusual fauna represented by fossils found in the Pysht Formation and which included plotopterids (an extinct group of flightless, penguin-like birds), the bizarre desmostylians (early relatives of seals and walruses), and toothed baleen whales.

Differences in body size, teeth, and other feeding-related structures suggest that simocetids likely hunted similarly to modern dolphins, using different strategies that relate to prey preference. “The teeth of Olympicetus are truly weird, they are what we refer to as heterodont, meaning that they show differences along the toothrow,” notes Dr. Velez-Juarbe, “This stands out against the teeth of more advanced odontocetes whose teeth are simpler and tend to look nearly the same.”

Still, other aspects of the biology of these early toothed whales remain mysterious, such as if they could echolocate like their living relatives. Some aspects of their skull can be related to the presence of echolocating-related structures, such as a melon—the iconic dolphin forehead. An earlier study had suggested that neonatal individuals could not hear ultrasonic sounds, so the next step would be to investigate the earbones of subadult and adult individuals to test whether this changed as they grew older.

About the Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County

The Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County (NHMLAC) include the Natural History Museum in Exposition Park, La Brea Tar Pits in Hancock Park, and the William S. Hart Museum in Newhall. They operate under the collective vision to inspire wonder, discovery, and responsibility for our natural and cultural worlds. The museums hold one of the world’s most extensive and valuable collections of natural and cultural history—more than 35 million objects. Using these collections for groundbreaking scientific and historical research, the museums also incorporate them into on- and offsite nature and culture exploration in L.A. neighborhoods, and a slate of community science programs—creating indoor-outdoor visitor experiences that explore the past, present, and future. Visit NHMLAC.ORG for adventure, education, and entertainment opportunities.

MEDIA CONTACT

For interviews and additional imagery, please contact Amy Hood, ahood@nhm.org