Los Angeles, CA (July 23, 2025)— Artists use layers of black and white paint to make their colors pop on the canvas, and it turns out birds are using the same technique. A study published in the journal Science Advances by a team of researchers from Princeton and the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (NHM) has found that some famously colorful songbirds dramatically enhance their vibrant plumage with secret underlayers of white and black plumage—“hidden achromatic feathers”. This discovery highlights hidden evolutionary tricks behind colorful feathers still waiting to be uncovered through advanced research techniques and bird specimens roosting in museum collections. The team found hidden achromatic layers in the feathers of many dazzlingly colorful and ornate songbirds—tanagers, manakins, fairy wrens, cotingas, and more—yet the evolution and optical significance of hidden achromatic feather layers have not previously been investigated.

Birds' brilliantly colored plumage helps them find mates, defend territories, and identify members of the same species. It takes thousands of individual feathers overlapping on the body like shingles on a roof to create a smooth and continuous display of dazzling colors. Yet even in the most colorful birds, individual feathers are generally colorful only at the tip. Beneath the colorful surface of the plumage, the feathers are typically drab, ending in a fluffy, grayish downy base. For decades, researchers have explored the colors and patterns present in the outermost layer of colorful plumage, assuming that the less colorful feather base primarily functions in insulation and has no impact on coloration, but this discovery reveals there is much more to colorful bird plumage than meets the eye.

“It’s one of those discoveries that you only notice when looking in detail at museum specimens, and that other biologists totally appreciate as soon as we tell them. It’s been right there all along, but no one has noticed,” says Dr. Allison Shultz, Ornithology Curator at NHM and expert on feather color. “Over the last few years, it’s become apparent that birds are modifying the colors of their feathers in ways that have flown under scientists’ radar for many years. It’s been really exciting in this study to show an additional way that has never been appreciated—by changing what essentially is the color of the base layer that the colorful parts of feathers lay on.”

The researchers initially noticed the hidden achromatic layers in male Tangara tanagers, a genus of South American songbirds famous for their color diversity. The research team took advantage of ornithological collections at the NHM, the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, and the Princeton Museum of Zoology, all of which house thousands of preserved bird specimens.

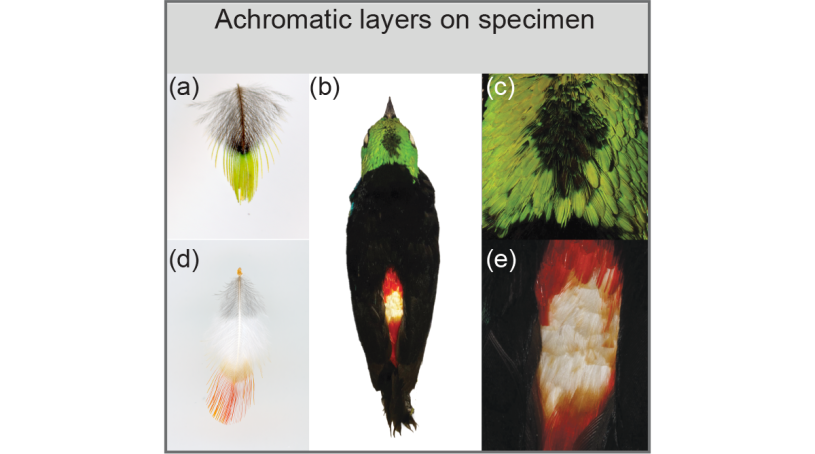

They began the investigations with microscopy and photography to document the achromatic layer in Tangara specimens, in some cases removing the colorful feather tips to expose the dramatic white and black layers concealed beneath.

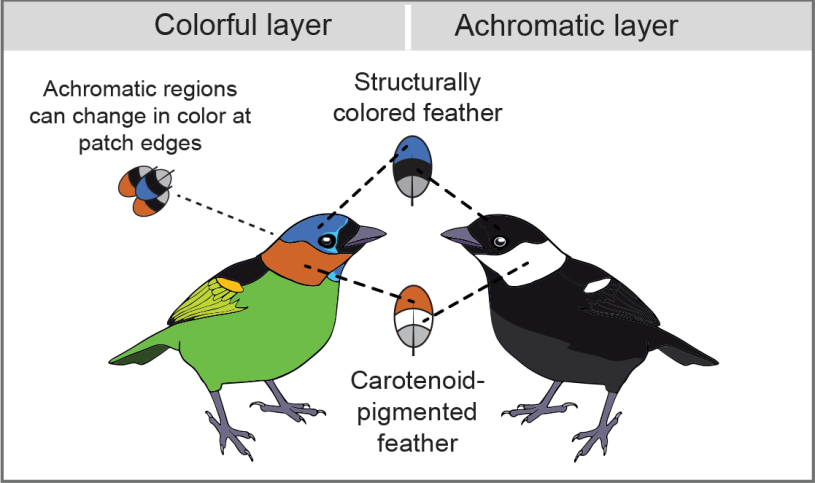

Remarkably, the team observed that the hidden layer's color varied systematically: it was white beneath red or yellow feather tips colored by carotenoid pigments—which produce color by absorbing different wavelengths of light—and black beneath blue or violet feather tips colored by nanostructures, whose shape reflects specific wavelengths to produce their colors.

To understand exactly how white and black layers affect the appearance of colorful feathers, the team sampled individual feathers from Tangara specimens and placed each feather on both white and black backgrounds. They used a range of state-of-the-art imaging techniques—including multispectral photography, microspectrophotometry, and hyperspectral imaging—to measure how feather tips change in color on white and black backgrounds.

They found that red and yellow carotenoid plumage is brighter on white backgrounds, while blue structurally colored plumage is more saturated on black backgrounds. To further explore this phenomenon, they used an optical model to simulate the appearance of colorful plumage while accounting for colorful, achromatic, and downy feather layers. “It might be surprising that we found a strong effect of the so-called 'hidden' background layer on the apparent color of the feather tips,” says co-author Benedict Hogan, an associate research scholar at Princeton, “But in fact, the effects were completely in line with optical theory.”

The Art of Nature

The technique of layering colors over white or black to make them pop is also used by human artists. Painters often include a layer of white gesso beneath the colorful pigmented paints layered on top, and makeup artists begin their work by applying layers of primer to skin.

“They say life imitates art. Quite often, art imitates nature. For example, glass artist Dale Chihuly is known to include a hidden ‘cloud layer’ of white glass to bring vibrance to the colours of his artwork,” says co-author Jarome Ali, postdoctoral researcher at New York University and former Princeton graduate student. “This is a fantastic example of where art and nature have arrived at the same means of producing fabulous colors.”

“As an artist myself, I’ve learned techniques for laying colors to achieve certain effects when painting. In fact, what first attracted me to birds and their colors was simply the beauty of their feathers. So coming back full circle to link art techniques with how birds are modifying their colors has been incredibly interesting and rewarding,” says Shultz,” says Shultz.

Why would a hidden layer of white or black plumage make colorful feathers on top appear more vivid? The answer lies in the physics of coloration. Red and yellow colors in plumage are typically produced by carotenoid pigments, which absorb some wavelengths of light but not others. Red colors are produced when carotenoids embedded in feather keratin absorb blue-green wavelengths, allowing red wavelengths to be reflected by the surrounding tissue. In contrast, blue colors are produced when nanostructures made of keratin and air within the feather selectively scatter blue wavelengths. That’s where the hidden achromatic layer of feathers comes in.

The researchers found that carotenoid-pigmented feathers—the red and yellow feathers—have a layer of white plumage underneath that reflects light back towards the surface, increasing the interactions of light with the carotenoid pigments in the colorful layer and enhancing the brightness the plumage. Structurally colored feathers—the blue feathers—have a layer of black plumage underneath which absorbs light that would otherwise be reflected back through the blue feather tips above, diluting the purity of the blue color reflected by the nanostructures.

“Tangara plumage is a beautiful mosaic of reds, yellows, greens, and blues,” says Rosalyn Price-Waldman, a postdoctoral research associate in Princeton’s Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and the lead author of the study. “Yet if you look beneath the colorful surface, you can see that there’s a remarkable patchwork of white and black hidden beneath, and it switches perfectly between white and black as the outermost colorful layer switches between carotenoid pigmentation and structural coloration.” It was this precise and systematic variation between white and black that first convinced the researchers that hidden layers of feathers might have an important optical function.

As a final step, the team examined hidden feather layers in a wide range of songbirds other than tanagers. They found that striking white and black layers have evolved in many colorful songbirds, yet they are absent from birds that display only brown, gray, and black plumage.

“We were intrigued to see how many distantly related birds have dramatic white or black layers concealed beneath their colorful outer plumage,” says Price-Waldman. “To understand the evolution and importance of colorful plumage in birds, we really need to be taking a closer look beneath the surface and appreciating the effects of hidden layers.”

Experimental approaches and optical modeling suggested that the hidden layers of feathers play a big role in altering coloration, but how biologically important is this effect? To answer this question, the team compared hidden achromatic layers between female and male Tangara tanagers. “Tangara females and males tend to look pretty similar, but males usually appear brighter—a phenomenon known as sexual dichromatism,” explains Shultz.

When they compared hidden achromatic layers between males and females, the team found dramatic differences in several yellow patches—males had white layers underneath their yellow plumage, but females had black layers. Even more surprisingly, the color of the feathers’ yellow tips was nearly identical between females and males when measured on the same background.

“Without accounting for the effects of white versus black achromatic layers, females and males would look extremely similar,” says Shultz. “That was very unexpected to us. Biologists often assume that sexual dichromatism in reds and yellows is due mostly to the pigment concentration and types in the feather tips. But we found, surprisingly, that these understudied hidden layers can produce substantial and potentially biologically meaningful variation in coloration.”

About the Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County (NHMLAC)

The Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County (NHMLAC) include the Natural History Museum in Exposition Park and La Brea Tar Pits in Hancock Park. They operate under the collective vision to inspire wonder, discovery, and responsibility for our natural and cultural worlds. The museums hold one of the world’s most extensive and valuable collections of natural and cultural history—more than 35 million objects. Using these collections for groundbreaking scientific and historical research, the museums also incorporate them into on- and offsite nature and culture exploration in L.A. neighborhoods, and a slate of community science programs—creating indoor-outdoor visitor experiences that explore the past, present, and future. Visit NHMLAC.ORG for adventure, education, and entertainment opportunities.

MEDIA CONTACTS:

Tyler Hayden

Science Communications Specialist

thayden@nhm.org

Amy Hood

Director of Communications

ahood@nhm.org