Los Angeles, CA (April 30, 2025)–A new study published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B by an international team of researchers has found that an ancient line of terrestrial crocodile-like creatures once reined over the Caribbean, filling an apex predator-sized hole in the islands’ ecological history with the first definitive record of a sebecid outside of South America during the Age of Mammals. Upending more than a century of debate about how vertebrates made their way to the West Indies, the finding suggests these ancient land-dwelling creatures walked from the continent along with the diverse menagerie of life in the ancient West Indies.

“We were thrilled when we found the teeth in the field in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic,” says co-author Dr. Jorge Velez-Juarbe of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. “But it was the moment we identified the vertebrae that confirmed our discovery beyond doubt—we had found Caribbean sebecids!”

In South America, there was an array of large predators like sebecids, enormous caimans, terror birds, and giant snakes, but in the West Indies, these were lacking. Sebecids split from crocodiles during the Jurassic and survived the mass extinction that claimed the dinosaurs. Their skulls were more like meat-eating theropod dinosaurs than their modern crocodilian relatives; they had a gait more like a mammal, and longer legs along with other adaptations for hunting on land. Analysis of their teeth from South America shows that sebecids sat at the top of the food web, dining on an array of terrestrial mammals.

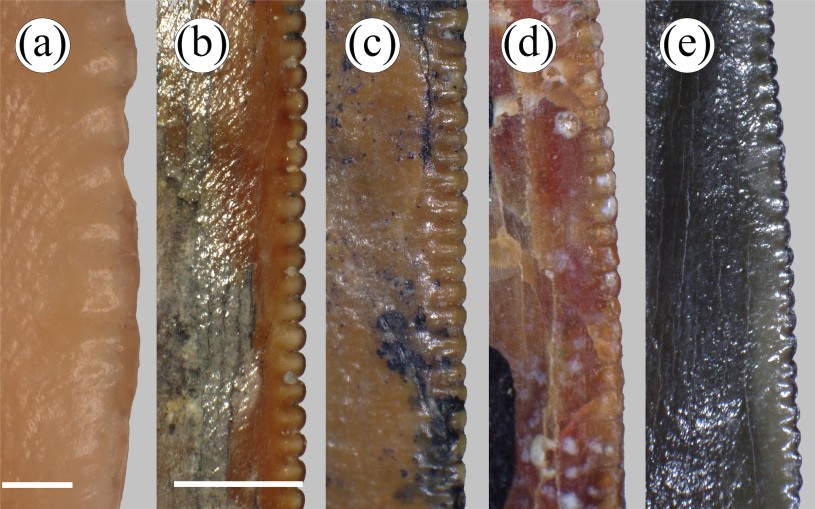

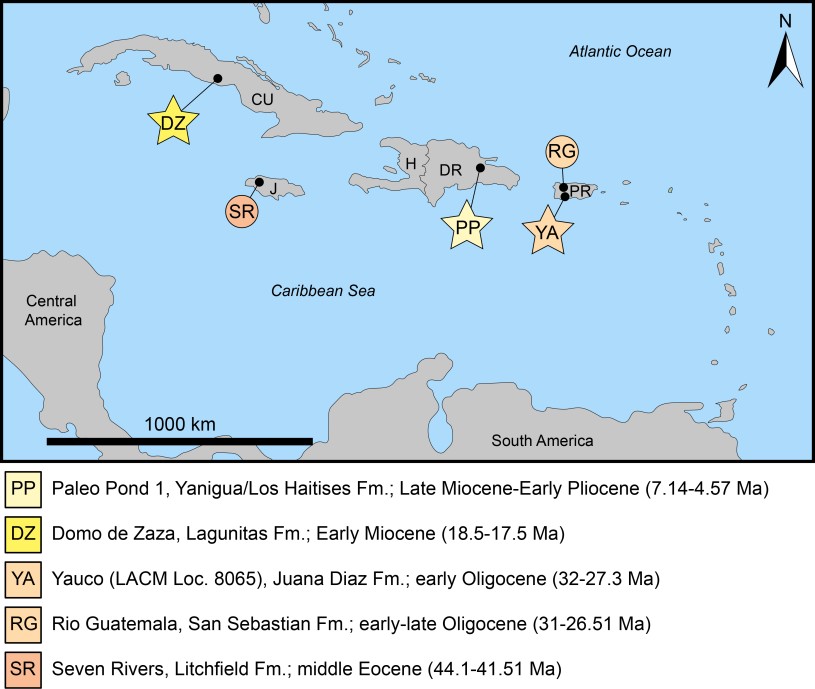

The international research team made the definitive identification through fossilized vertebrae and multiple teeth from Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and Puerto Rico. The specialized saw-like teeth—serrated for rending flesh—clearly identified the specimen as a crocodile relative, but three different groups had independently evolved these specialized teeth, so identifying the ancient croc was difficult at first. The team compared CT scans of the specimens with fossil records from the West Indies, North and South America, and taking into account the geographical and geologic timelines, it was highly suggestive that they were looking at sebecids. While the teeth shared many characteristics, it was the vertebrae that confirmed their identity as belonging to sebecids.

The study marks the first record of a sebecid outside of South America in the Cenozoic—the Age of Mammals that began roughly 66 million years ago. While sebecids date back to the Cretaceous and survived the asteroid and subsequent mass extinction of the dinosaurs, they finally died off in South America around 11 million years ago due to changing climate and vanishing habitats. Surprisingly, the study finds they survived considerably longer in the ancient Caribbean.

“Much like their counterparts on land, apex predators on islands are crucial for preserving ecological balance among native and endemic species,” says Dr. Velez-Juarbe. “Throughout Earth’s history, crocodiles and their extinct relatives have filled this role time and again across both continents and islands. Discovering that sebecids once reigned as apex predators in the Caribbean was an exciting surprise!”

Walking to Island Refuges

The lack of an apex predator in the West Indies had fueled the argument against a land connection between ancient South America and the West Indies, but the discovery supports a journey overland for the islands’ vertebrates. Just as rising sea levels reshape our modern coasts, the ancient Caribbean was subject to changes in global sea level, which, combined with the rising of regional landmasses, resulted in a path for South American vertebrates to cross into the West Indies, resulting in the diverse life found on the islands. Researchers argue that local tectonic events combined with lower sea levels cleared the path around 33 million years ago, whether that connection was through a continuous landspan or a closely spaced group of islands is still up for debate. Still, the presence of an apex predator adapted to life on land makes the former argument more likely.

Sebecids would have shaped life in the West Indies both in their presence and absence. Islands have a long and well-known track record as safe harbors for species that die off on the mainland, acting like natural biodiversity museums. While climate change and habitat loss claimed their continental relatives, sebecids on the West Indies hung on for at least five million more years. As the last of the sebecids vanished from the West Indies, their last stop before exiting the planet, other predators arrived to fill the void over the intervening millions of years, reshaping the food web into the one we know today.

“We’ve long suspected that crocodyliforms played a far more significant role in shaping the ecology of ancient West Indian faunas throughout the Cenozoic, but much of their story remains untold,” says Dr. Velez-Juarbe. “Fieldwork in the tropics can be demanding but highly rewarding, so we are fully committed to continuing our explorations across the Greater Antilles. Who knows what other surprises await us, helping to unravel the complex origins of the Greater Antillean terrestrial fauna?”

MEDIA CONTACT:

Tyler Hayden

213-763-3508

thayden@nhm.org

Amy Hood

213-763-3532

ahood@nhm.org